Executive Summary

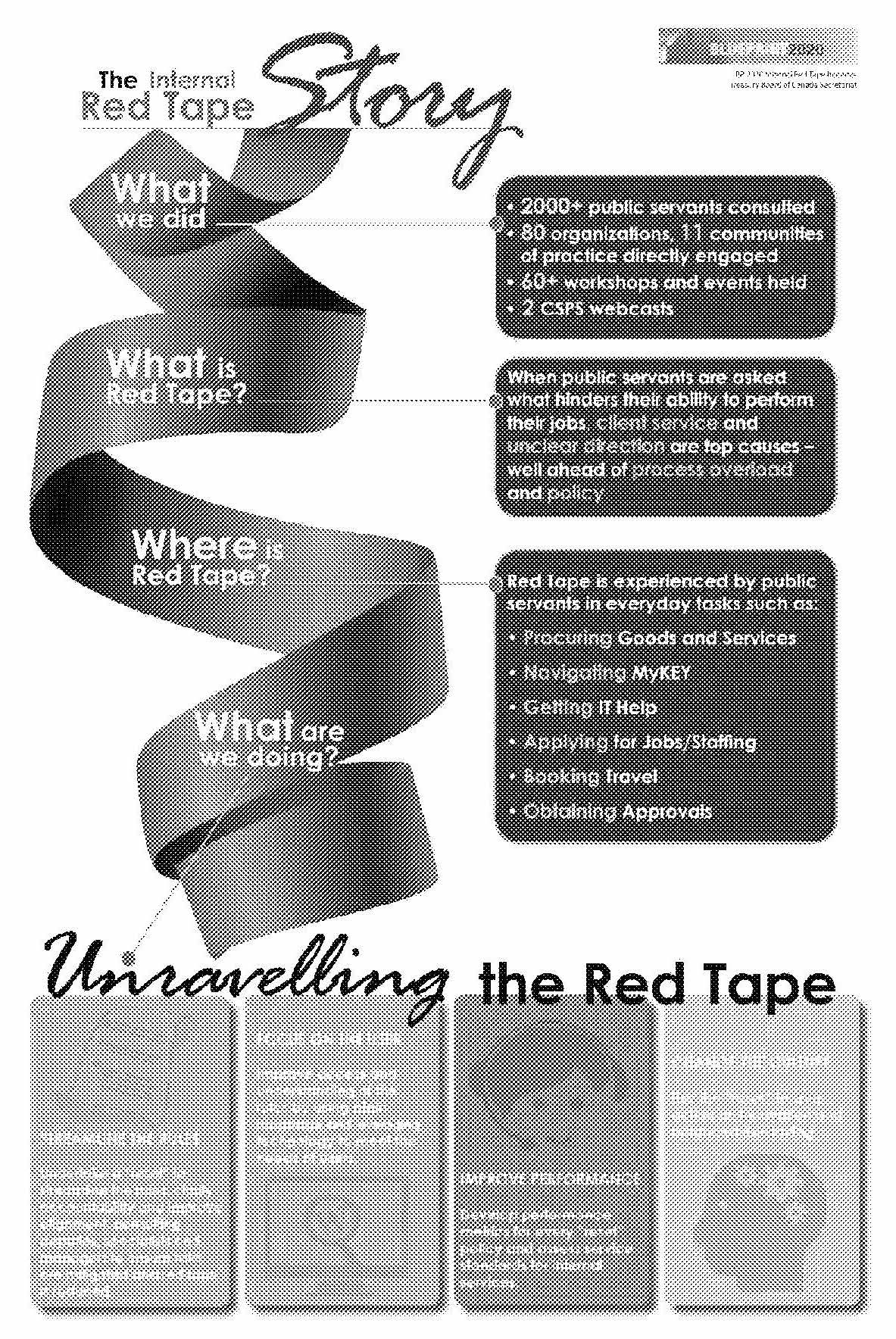

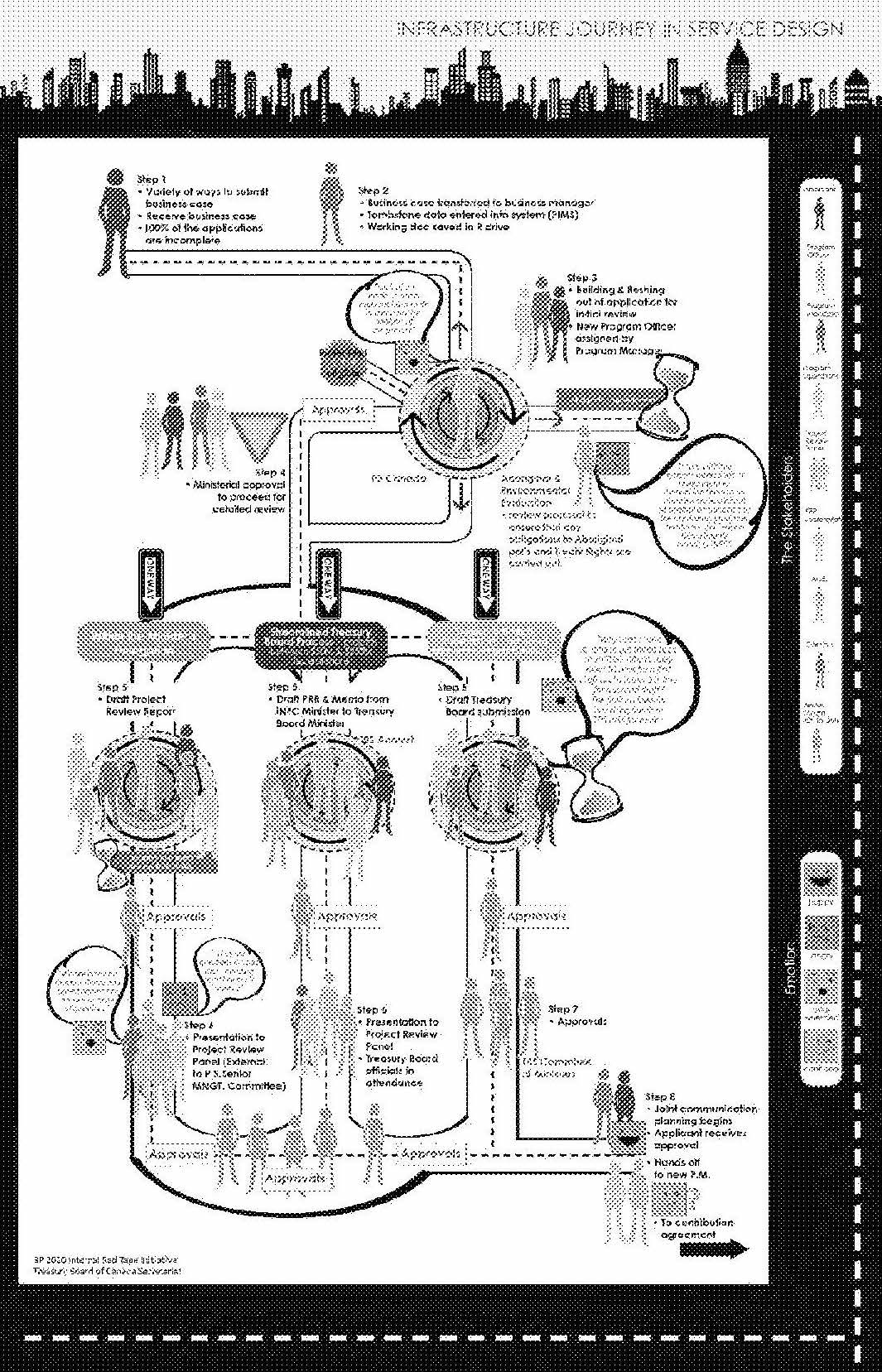

During the Blueprint 2020 discussions, public servants reported that many rules and processes were overly complex, top-down and lacked coherence. Subsequently, simplifying internal processes and reducing internal red tape was identified as one of the five priority areas of action in Destination 2020. To this end, a small multi-disciplinary Tiger Team was established at the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) to engage public servants from the “bottom up” using social media and roundtables to identify the common irritants and to design solutions to address them. The diagram, “The Internal Red Tape Story,” provides a snapshot of what the team accomplished over the two-year span of the initiative by adopting a user-centric design-thinking approach. This report presents key findings and recommendations that reflect the voices of public servants.

Key findings

Judging from the scope and intensity of the input received, internal red tape is a significant issue for public servants in all departments and in all regions. Public servants broadly recognize that in a large, complex organization such as the federal government, rules help ensure good stewardship, governance and accountability. However, while they recognize the need for rules, public servants noted that the current rules, policies and guidelines are difficult to find and, once found, difficult to understand. This judgement applies to both Treasury Board policies and the vast number of rules created by departments to supplement them.

When asked to describe their experiences with internal red tape, they identified a broad range of things that hinder their ability to perform their jobs. Internal red tape is much more than just the rules; it encompasses the behaviour around the rules. It manifests itself in difficulty getting clear instructions, with siloed information, experiencing poor client service and, ultimately, process overload. It is worth noting that recent technological solutions that had been introduced – such as MyKey, performance management, and the travel portal – were cited as sources of frustration.

Deeper dives into the underlying causes of internal red tape found broad repeating themes. Departmental processes and procedures are often more elaborate than required by Treasury Board policy. Transactions generally follow similar cumbersome processes, irrespective of the level of risk, and existing flexibilities are rarely used. And fear of audit is often cited as a driver for procedures and demands for documentation. This has created an environment where client service takes a back seat to process. And finally, both functional specialists and clients stated that they feel powerless to change the system.

Key recommendations

-

Improve the rules – Use the current Treasury Board Policy Suite “reset” exercise to streamline rules and clarify accountabilities. Departments should then review their internal departmental policies to ensure they are not duplicative or creating unnecessary burden.

-

Focus on the user – Make it easier for public servants to follow the rules by providing information, guidance, training and tools that meet the needs of users, including both functional specialists and their clients. Ensure that any technological solution is designed with the user in mind, is user tested and has a feedback loop for improvement.

-

Improve service performance – Develop robust performance measures that prioritize client service standards to counterbalance the focus on rule-following and compliance. A service strategy for internal services is critical if internal red tape is to be reduced.

-

Change the culture – Resist behaviours and incentives that drive red tape, such as the tendency to react to events by layering controls and processes. Allow for flexibilities and adaptable practices that respond to the level of risk for a transaction. Reward desired behaviours.

Structure of this report

This report is structured as follows. Chapter 1 sets the context for the initiative. Chapter 2 describes the characteristics of internal red tape and proposed solutions to address them. Chapter 3 centres on the root causes of red tape in three areas. Chapter 4 offers some lessons learned from the initiative. The engagement process, tools used in the initiative, snapshots of internal red tape stories and a service strategy for internal services are in the Annex.

Chapter 1: A call to action

In June 2013, Blueprint 2020 (BP2020) was launched, setting in motion an unprecedented engagement exercise with public servants about the future of the public service of Canada, with “the goal of ensuring that it remains a world class institution.” During the dialogue that took place in the weeks following the launch of BP2020, public servants reported that…

“Many rules and processes are overly complex, top-down, siloed, and lack coherence and consistency. This often results in a frustrating experience for those trying to do their jobs.”

In May 2014, the Clerk of the Privy Council stated in the Destination 2020 report that simplifying internal processes and reducing internal red tape would be one of five priority areas of action taken to transform the federal public service for now and the future.

To this end, the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) was tasked with establishing a small multi-disciplinary Tiger Team to engage public servants using social media and roundtables to identify “some of the biggest specific irritants.” Moreover, on red tape problems that are complex, the Tiger Team was called to work with departments and agencies to look at all aspects of rule-making in order to find solutions.

A small multi-disciplinary Tiger Team was established at TBS in the summer of 2014. A two-year work plan was developed subsequently. Engaging and collaborating with public servants was at the core of the initiative. The reason was twofold. First, while internal red tape was raised during the Blueprint 2020 engagement exercise, the comments were too general to really identify the specific problems. Second, to achieve the Destination 2020 objective of improving “the experience of those who must follow the rules and administrative processes,”’ it was essential to involve them in the problem-solving process. Instead of consulting public servants with a pre-prepared diagnostic, the team adapted a user-centred design-thinking process by first identifying the problems with public servants.

Project timeline

Launched in November 2014, the internal red tape reduction (IRTR) initiative consisted of two phases:

- engaging public servants to identify the biggest irritants; and

- exposing root causes in a few areas with relevant departments and agencies.

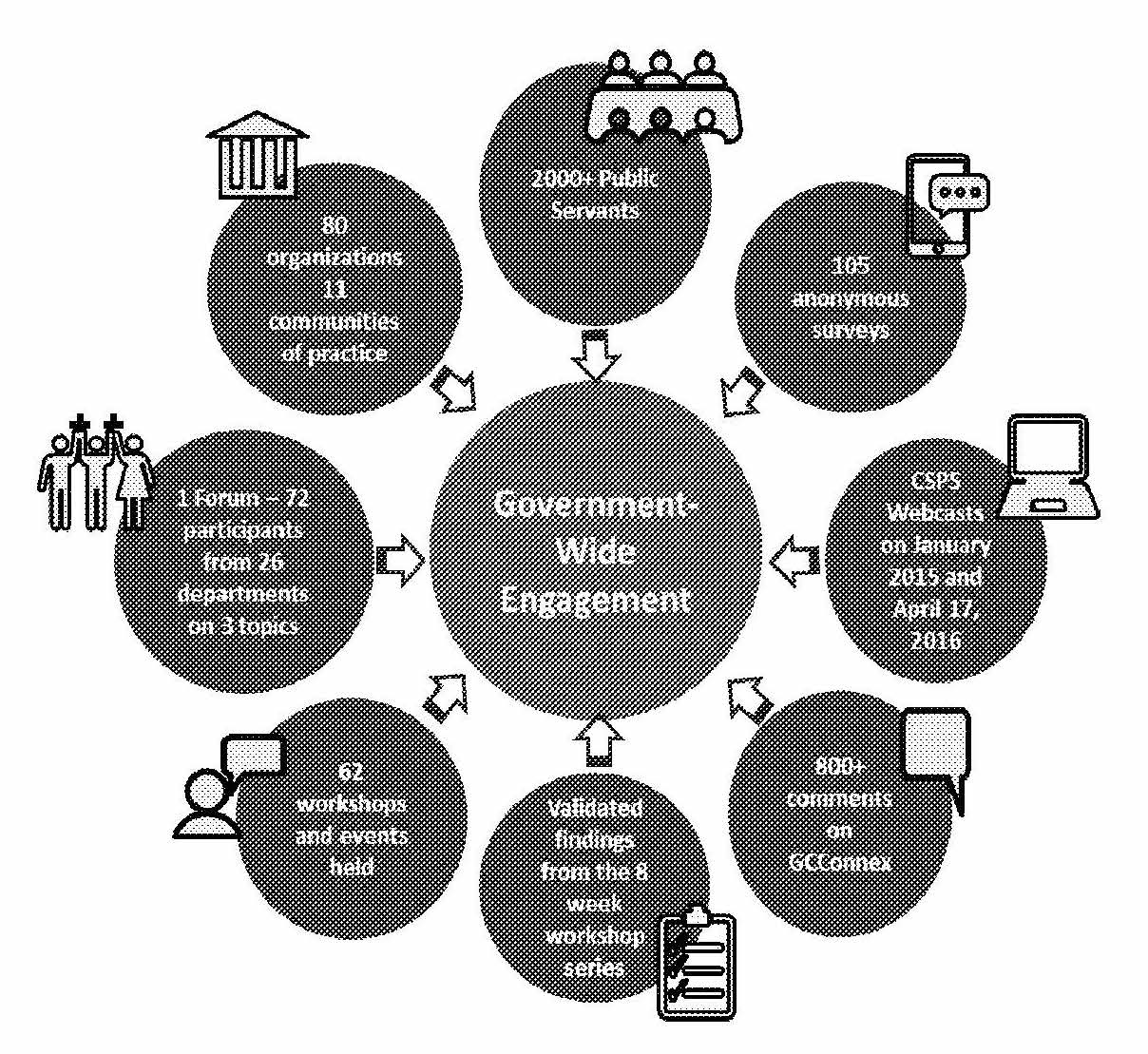

The broad engagement exercise reached more than 2,000 public servants across the country through discussions and workshops, both online and in person. These interactions helped identify the nature of red tape and where it occurred most often. The results were shared during the first national webcast on internal red tape reduction, hosted by the Secretary of the Treasury Board with deputies from partnering departments in April 2015.

During the webcast, public servants were asked to identify the top three areas where reducing red tape could improve their experiences in a tangible way. Staffing, procurement, and grants and contributions were the most mentioned areas. Subsequently, the Tiger Team convened an interdepartmental forum with a focus on these three areas. Seventy-two individuals from 26 departments and agencies attended this one-day event, where they got to share their current work in any of these three areas and collaborated on solutions by applying design-thinking tools. Following the forum, three interdepartmental working groups were formed. Over eight weeks, each team delved further into one of the three areas with a view to exposing the root causes and ideating solutions. The diagram, “Engagement of Public Service at a Glance,” illustrates what was accomplished through the project. A step-by-step description of the initiative can be found at the end of this report.

A word about design-thinking

As shown in Figure 1, design-thinking puts users at the centre of a problem-solving process. To analyze a problem, this approach centres on understanding it from the perspective of users by listening to their points of view and developing the analysis with them. Once a problem is identified, it focuses on designing solutions with those who will be affected by the solutions instead of providing a solution for them. (See Figure 1.) The methodology for this initiative will be described in the Annex.

Chapter 2: Unravelling internal red tape, one story at a time

In brief

Engaging public servants at the working level

A key element of the Engagement Phase was to listen to public servants at the working level about their encounters with internal red tape in order to identify common irritants. A variety of engagement channels were used to reach as many public servants as possible, in departments and agencies, communities of practice and networks. The Tiger Team sparked discussions online through blogs and discussion groups on the Government’s social media platform, GCconnex, under the group Blueprint 2020 – Reducing Internal Red Tape. The team held virtual and in-person workshops, and also provided public servants with the opportunity to participate anonymously via survey. Through these efforts, the Tiger Team reached more than 2,000 public servants, collected over 400 stories and boasted the most active participation rate on GCconnex, averaging eight interactions per day (e.g., comments, likes, blog posts).

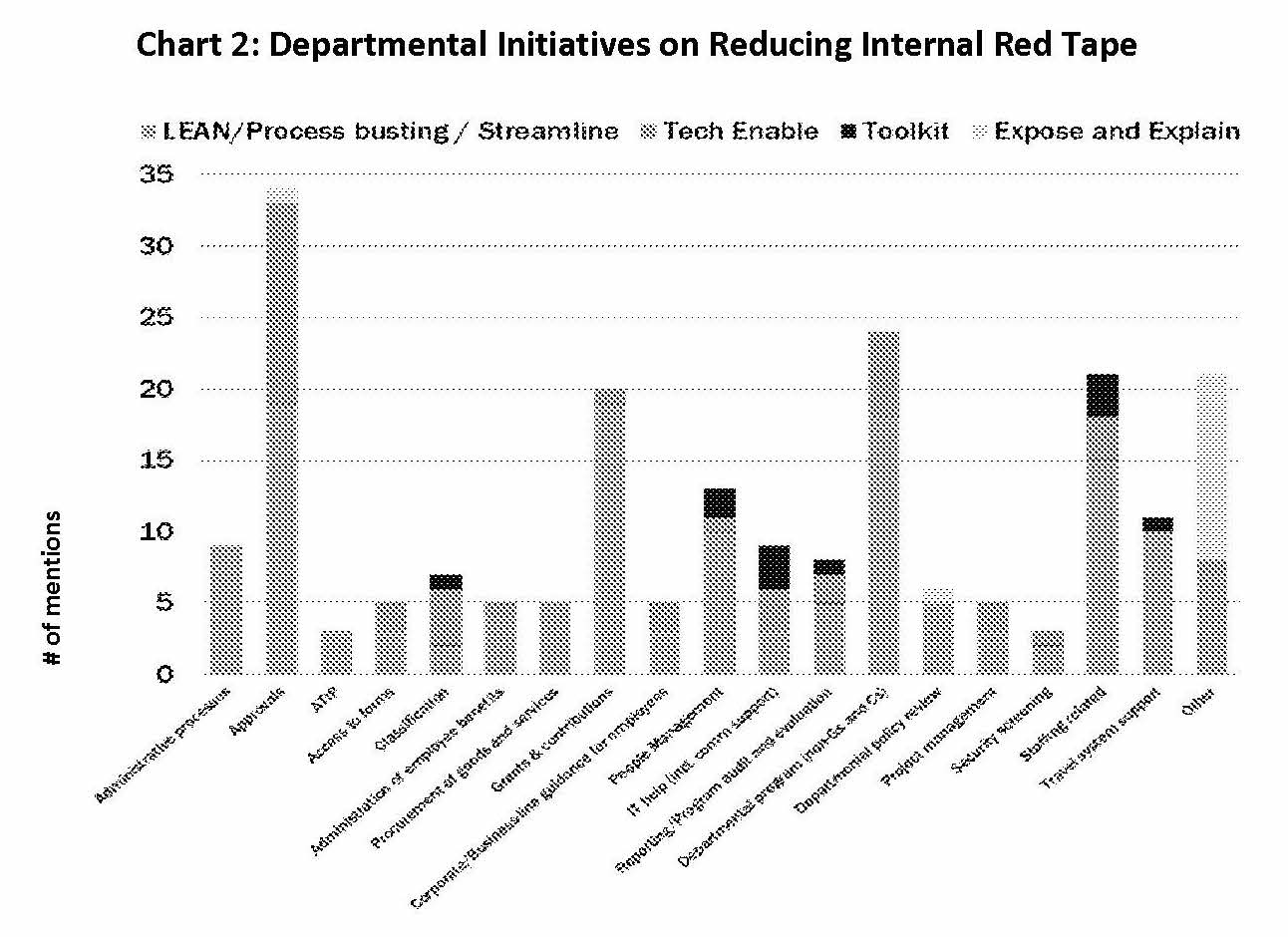

In addition to describing the problems they encountered, public servants were asked how they would solve them in order to improve their experiences. Public servants were also asked whether some of the barriers (or “red tape”) they experienced were being addressed in their respective organizations or within the public service. It became evident that many organizations were already undertaking initiatives to streamline processes internally. As a result, the Tiger Team broadened its scope to include surveying those activities taking place across government. Over 170 initiatives across 45 departments were collected.

Internal red tape occurs in the tangential elements of day-to-day working life

Public servants encountered barriers in the tangential elements of their day, such as getting IT help, filling out a travel request, evaluating performance, and accessing electronic systems after new software was introduced. Changing departments was another major area where red tape was found, as this requires public servants to complete security clearance forms and reactivate their myKEY, which gives them secure access to government applications, including the Compensation Web Applications.

These are a few examples that have been brought forward, among many others. A snapshot of these internal red tape stories is available in the Annex of this report.

Unclear direction / burdensome policy and poor client service are top causes

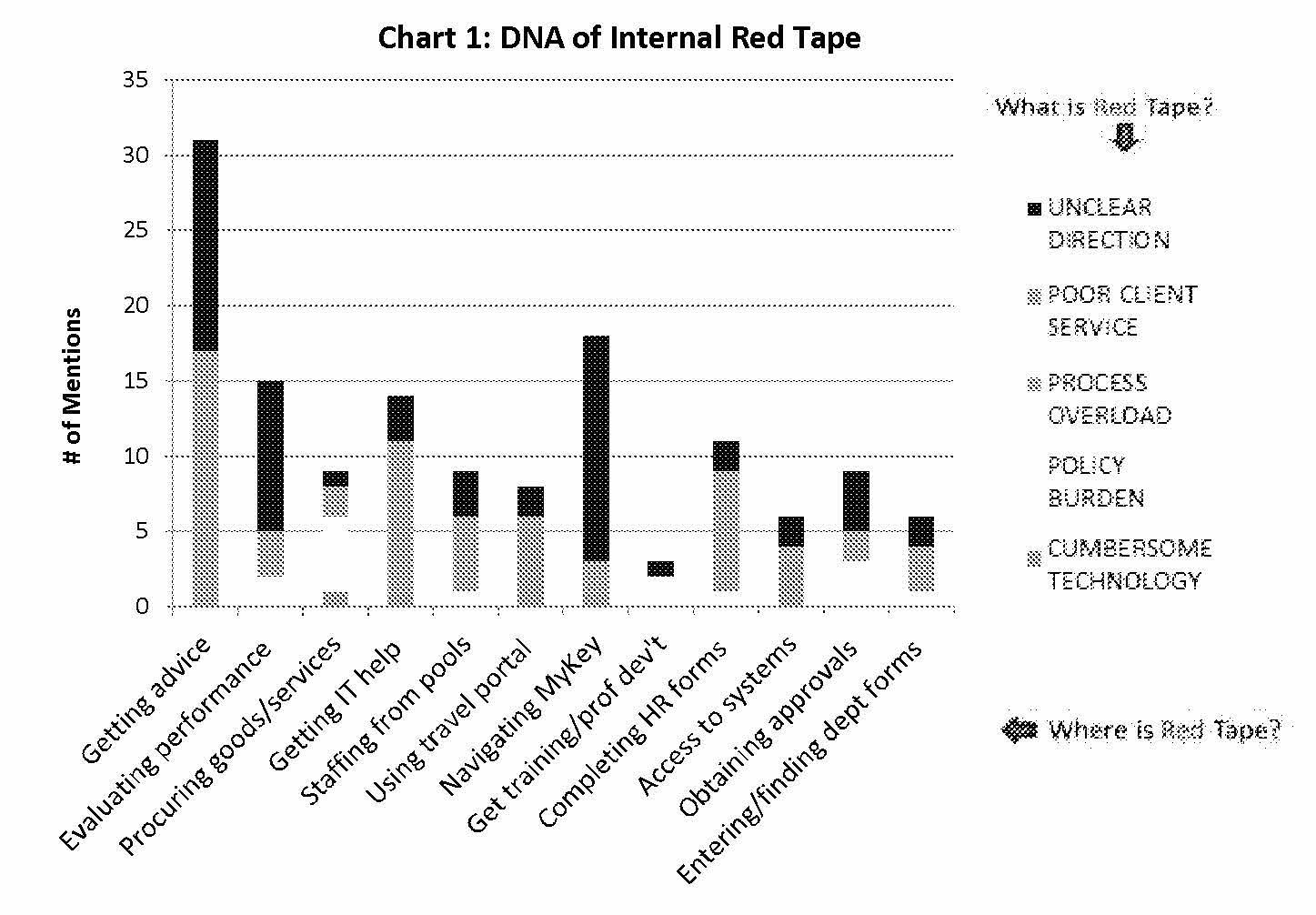

Complicated processes, paperwork and policies often come to mind when talking about red tape. However, the findings from Phase I tell a slightly different story (see chart of DNA of internal red tape). When public servants were asked what hinders their ability to perform their jobs, unclear direction/burdensome policy and poor client service were top causes, even ahead of process overload. In contrast to what was assumed to be the case, policy plays a lesser role in the red tape story from the public servant’s point of view. The analysis further showed that the usability of technology linked to enterprise-wide initiatives, such as the performance management portal, myKEY, and the travel portal, was viewed as a hindrance. Further, this task contributed to more types of red tape.

Departmental efforts to reduce internal red tape are not addressing the key issues raised by public servants

In response to the Blueprint 2020 feedback, many departments had initiated internal red tape reduction exercises of their own. As the Tiger Team began cataloguing those activities, it became evident that many of the issues being worked in departments aligned with problem areas identified by public servants: procurement, staffing, internal processes and approvals. However, the solutions being proposed focused on streamlining processes (through LEAN and other methods), introducing technological solutions and producing toolkits. These initiatives were not addressing the primary pain points identified by public servants: unclear direction and poor service. Moreover, departments were working on similar problems in isolation, with limited sharing of experience and best practices.

Addressing the root causes of the irritants requires a multi-pronged approach

“ …senior leadership is going to do everything it can to make sure that the rules, the structures, the policies are enabling and empowering, that we get rid of bureaucracy and process for processes’ sake, rules for rules’ sake.” – Michael Wernick, Clerk of the Privy Council, at APEX Symposium 2016.

Addressing red tape in the federal public service will require a multi-faceted approach. As the stories suggest, the issues are shared, and there is no one simple solution to lighten the red tape load. Just as the issues are shared, the solutions depend on central agencies, departments and functional communities working collaboratively together to reduce the instances of internal red tape that hinder public servants in performing their jobs on behalf of Canadians every day.

Many layers that contribute to red tape have been identified. By focusing on each component that makes up red tape, we will be able to formulate a solid approach to making improvements.

Unclear direction / burdensome policy

What we heard

Public servants indicated that rules, policies and guidelines are unclear and difficult to find. As a result, departments apply their own interpretations, oftentimes not leveraging existing flexibilities and adding burden.

As shown in the DNA of internal red tape graph, “unclear direction” and “burdensome policies” are two of the most common barriers identified by public servants. If “unclear direction” is the foundation of the irritants, this is a clear indicator that we need to improve the ability of public servants to find rules, procedures and guidance. These must also be written in plain language, easy to interpret and, where applicable, accompanied by user guides and/or how-to videos.

Policy is a broad topic that affects public servants in different ways. Through the broad-based consultations that the Internal Red Tape Tiger Team (Tiger Team) conducted, stories were gathered regarding strict policy and the impact it has on public servants in their day-to-day operations. It affects everyone in different capacities: at a departmental level, through various occupational groups, and from a regional and National Capital scope. Policy in the federal government is designed to create rules that are easy to follow and minimize risk. Departmentally, however, certain policies are interpreted differently, causing the rules to be more rigid than they are intended to be.

Proposed way forward

Proposals to address the issue of lack of clarity include focusing on improving access to information through an enhanced, user-focused web presence. This would entail sophisticated search capabilities to close the knowledge gap between functional specialists and other public servants, and the ability to link information together. Additionally, the web presence should link to Canada School of Public Service (CSPS) training, such that employees are in direct contact with the School. This will ensure awareness of training and learning opportunities across the public sector. The new “Policy Suite Reset” website, released on June 6, 2016, is a step in the right direction. With time, its increasing functionality will improve the ability of the user to find and understand Treasury Board rules. However, there is a need to build more capacity at the working level to solve problems and identify innovative approaches. The Web 2.0 tools offer a venue, but their use is still very preliminary, and even if they become good tools for functional communities, there is also a need to include public servants.

Through the user-centric Policy Suite Reset, work is under way to review the Treasury Board Policy Suite in order to eliminate unnecessary requirements and reduce burden. Work is also under way to ensure that policies are written in plain language and understood by users. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) is committed to having a clear and more understandable suite of policies.

As TBS works on the policy suite, it will be important for departments to review their own internal departmental policies through a user-centred approach, to ensure they are leveraging available flexibilities and do not end up creating additional departmental policies.

Poor client service

What we heard

“Poor internal client service” was a frequently-mentioned irritant identified by public servants during Phase I and the broad-based consultations. More specifically, the stories that the Tiger Team captured reveal that there is a lack of acknowledgement regarding how critical a culture focused on internal client service is to a successful organization.

Public servants told us that they experienced the following when accessing internal services:

- Client must initiate contact;

- Lack of support and guidance;

- Conflicting or unreliable advice;

- Local expertise ignored; and

- Multiple contacts and a “not my job” mentality.

As the federal government has centralized most of its services, many individuals shared their concerns about not being able to speak directly to a person, but rather having to send enquiries to a central mailbox via email, where responses are bounced around without the provision of consistent or appropriate information. Further, this also resulted in siloed information when specialized call centres were only able to answer a portion of the issue. These findings underscore the importance of focusing service excellence on internal services.

Proposed way forward

Concerted attention on developing and supporting a culture of service for internal services is considered to be critical to any effort to reduce internal red tape. It is recommended that a service strategy be developed for internal services, thus signaling the Government’s commitment, through Blueprint 2020, to improving the working life of public servants. This would entail:

- Redesigning service offerings to meet client needs;

- Engaging clients in service design and improvements;

- Setting service standards and client satisfaction targets;

- Investing in people;

- Measuring, monitoring and benchmarking service performance;

- Establishing a service excellence community of practice for internal services; and

- Communicating and marketing the Government’s commitment to service excellence in internal services.

Of note, the Management Accountability Framework (MAF) has included a few questions about service standards in its methodology. Early results indicate that many departments with service standards do not track performance against them and that there is no common way to measure performance for similar activities across departments. As a result, there is a wide range of results for similar tasks. For example, the days required to staff an AS-01 position range from 2.3 days to 195 days, and the mean time required to repair workplace technology device (WTD) related incidents ranges from 1 to 284 hours in the 37 large departments and agencies assessed in 2015-2016. The MAF will continue to promote internal service standard indicators within its methodology. While more work is required to arrive at fully comparative results, they serve as a starting point and could support a government-wide strategy for improving service delivery for internal services.

Process overload

What we heard

Accomplishing a single task involves undertaking too many steps and unnecessary processes. Through the analysis conducted in Phase I of the project, process overload was among the top three irritants which public servants indicated as having a serious impact on getting their jobs done. Stories and interviews that were collected detailed how accomplishing a single task involved undertaking many steps and unnecessary processes. Also, many individuals working in the regions have expressed their frustrations and concerns with their daily tasks, which are riddled with added process and longer wait times because they are far removed from National Headquarters.

Proposed way forward

Looking at the work currently under way in departments, it is clear that a lot of effort has gone into streamlining processes. As this continues, it may be helpful for departments to adopt a “show me the rule” approach, by empowering employees to seek justification as to why things cannot be done differently. The work environment should be such that employees have the ability to have an open dialogue with their managers so that decision-making is inclusive and gives employees the capacity to challenge processes that are cumbersome or that do not make sense.

It is also important, when scrutinizing processes, to ask service providers and clients what is working and what is not working by establishing feedback mechanisms to obtain the information and to determine sun-setting clauses to rules and proceed with change management exercises in order to change established practices. The users of the processes, both frequent and infrequent, are essential to having a successful streamlining exercise.

While streamlining processes is a necessary step, such efforts will only be temporary if the underlying culture and desire to add steps are not addressed. In addition, when the right conditions exist, departments may need to favour a risk-based approach to oversight and review. This can be done by establishing ongoing monitoring based on sampling rather than reviewing 100% of the transactions. This will provide sufficient documentation for audits and internal controls, as well as alleviate the time and pressure to overlook all processed documents.

Cumbersome technology

What we heard

The technology solutions introduced are not sufficiently user tested or intuitive. Technology, with all of its power and potential, was flagged as one of the barriers hindering public servants attempting to get their jobs done. A common argument and pain point expressed was that technology often gets rolled out to create efficiencies in business processes but, more often than not, it lacks the capacity to meet the users’ needs. As time is always of the essence, technological solutions get rolled out without adequate user testing or training and are not always intuitive. Countless frustrations surfaced when consulting with users, indicating that individuals are forced to conform to centralized technological solutions, such as GCDocs, the travel system and myKEY, which are implemented without the business process being designed with the users’ needs in mind.

Proposed way forward

Moving forward, it will be essential to dedicate ample time to the involvement of users in the early stages of designing technological solutions before they are implemented across government, to ensure that users’ needs are met. This would involve incorporating usability testing and user engagement at the outset of business planning so that those who will be using the technology can make known their needs to ensure efficiency and money well spent. In addition, it is imperative to dedicate sufficient attention to user testing and implementation of new technology. More often than not, more time is spent on establishing the concept rather than on the implementation.

As many of these technological solutions are already in place (e.g., travel system, myKEY, PSMP, MyGCHR), it is critical to establish a formal mechanism to obtain regular feedback from the users on what is working and what could be improved. The feedback received would then feed into system improvements.

Lastly, although training, user guides and/or online tutorials are often made available when new technology gets released, it would be beneficial to test the material with users with varying levels of proficiency before rolling the material out to the entire public service. Some questioned the wisdom of overlaying technology onto overly complex business process, suggesting that business processes be streamlined before technology is adopted.

Chapter 3: Exposing the root causes of the irritants

In brief

Enabling interdepartmental collaboration

In Phase II, TBS established interdepartmental working groups comprised of both “rule makers” and “rule followers” to perform a deep dive into three areas: procurement, staffing, and internal processes for grants and contributions.

To mark the launch of Phase II and serve as a first step toward addressing the key findings of Phase I, the Tiger Team held a one-day forum that brought together 72 participants from 26 departments, all working on projects related to these areas. The Forum also brought together policy specialists in the three areas from Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) policy centres and the Public Service Commission to provide expert advice about the rules. Participants also included a cross section of users: hiring managers and public servants with experience in contracting. The purpose of the forum was twofold:

- to gather representatives from across government who were working on process simplification projects in these areas, in order to learn from each other’s experience, share best practices and explore different approaches to problem solving; and

- to identify individuals and departments interested in working with the Tiger Team as they moved forward to the second phase of the initiative.

The core of the day’s activities had participants working together to address common challenges, while learning design principles to help them think more broadly about how to reduce internal red tape. These learnings were then used to work together on common areas of interest.

The results of the forum’s collaborative activities formed the three-stream basis for Phase II: Exposing the Root Causes of Irritants:

- The Internal Advertised Staffing Process with a National Area of Selection

- Low Dollar Value Procurement (under $25,000)

- The Internal Grants & Contributions Process

The Tiger Team established Interdepartmental Working Groups in each area. Through an eight-week workshop series, participants applied user-centred design thinking tools to identify the root causes of irritants and expose the pain points, as experienced by users of the processes being examined. In general, participants gathered critical information through interviews with program officers in participating departments, as well as by identifying stakeholders and mapping out the processes associated with the task. In doing so, Working Group participants were able to expose the root causes of internal red tape in each area and design possible solutions to move forward.

The methodology used during the workshop series is explained in the Methodology section of this document.

Common root causes of internal red tape

The departmental participants working in the three streams were drawn from various functional areas and a broad range of departments. They began by identifying the legislative and policy drivers – in most cases, each stream was subject to diverse legislative and policy imperatives. As the work progressed, it became clear that the root causes of the internal red tape shared common characteristics.

Of note, departmental processes and procedures were more elaborate and restrictive than required by either Treasury Board or Public Service Commission policies. Instead of using the flexibilities that existed in the policies, departments interpreted and applied policy requirements in the strictest sense. Transactions often followed the same internal process, resulting in a level of scrutiny that often outweighed the risk.

In many cases, departments had limited tools to support the process. Although basic policy requirements remain stable, there is a perception that they are constantly changing because of constant adjustments to rule-related procedures and paperwork. Clients often lacked knowledge in the area (e.g., procurement or staffing) because it was tangential to their day-to-day work and become overwhelmed by procedures and paperwork. Fear of audit was repeatedly cited as the driver for increased procedures and demands for documentation. This encourages a risk-averse culture where the functional groups play more of policing function rather than a client service provider role.

Finally, both functional specialists and clients reported being numb to the process and feeling powerless to change the system.

Procurement stream findings

Participating Departments

- Transport Canada

- Infrastructure Canada

- Department of National Defence

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Central Agency Partners

- Office of the Comptroller General

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

Scope: Procurement of a low dollar value (LDV) service contract under $25,000

Background

A majority of service contracts (89%) issued by the federal government in 2013 were valued at under $25,000, even though they only account for 8.7% of the total value of all contracts of the year (including goods, services and construction). Although not required, 53.7% of all contracts under $25,000 are awarded through a competitive process.

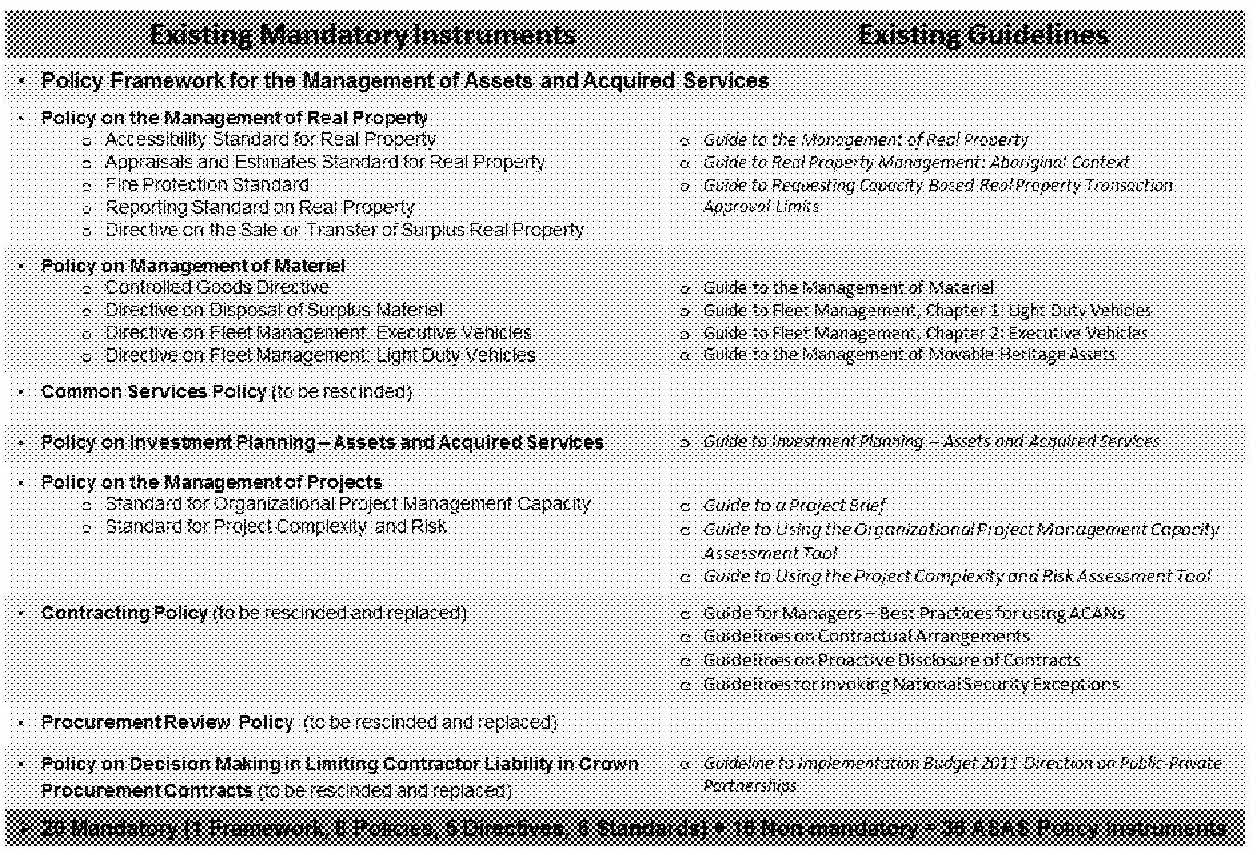

A series of policies, standards and guidelines applies to the area of procurement. Treasury Board’s current Acquired Services and Assets policy suite includes 20 mandatory instruments (one framework, eight policies, five directives and six standards) as well as 16 non-mandatory ones, for 36 policy instruments in total. Refer to Table 1 for a list of policies under the Acquired Services and Assets policy suite.

The main Treasury Board policy that governs procurement is the Contracting Policy, which has been in effect since 2006 and is currently under review. Many other policies that impact procurement have been put in place over the years and add new requirements, depending on the nature of the goods to be purchased (e.g., controlled goods, fleet) or the services to be acquired (e.g., security, intellectual property, official languages). There are also a substantial number of trade agreements, which include legal obligations on competitive tendering, time limits for bidding, performance-based specifications, the use of electronic tendering, and bid dispute mechanisms. Likewise, there are other legal agreements that are meant to promote socio-economic benefits for certain social groups (e.g., Land Claim Agreements, a Procurement Strategy for Aboriginal Business), industrial regional benefits, and measures to create opportunities for small and medium enterprises.

Not including internal departmental policies and guidance, there are over 35 different types of legal and policy instruments affecting procurement. Policies on the management of projects, real property, investment planning and other Treasury Board (TB) policies, such as the TB Policy on Government Security, also have an impact on procurement. As a result, procurement officers must navigate through complex and overlaying rules, many with specific social or economic policy objectives. However, there is one area of procurement in which the rules are simplest: LDV procurement.

The problem: Low return on investment on low dollar value service contracts

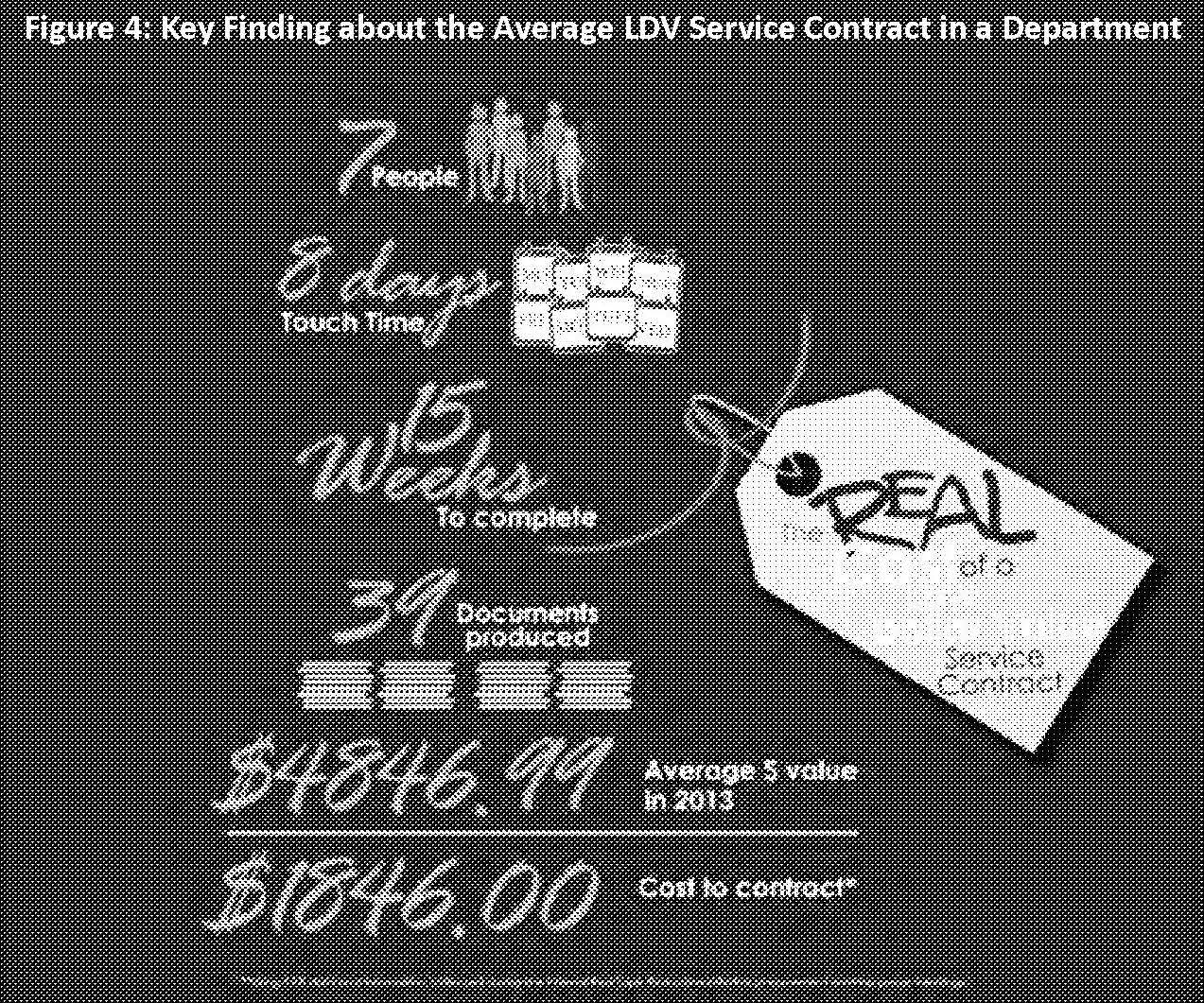

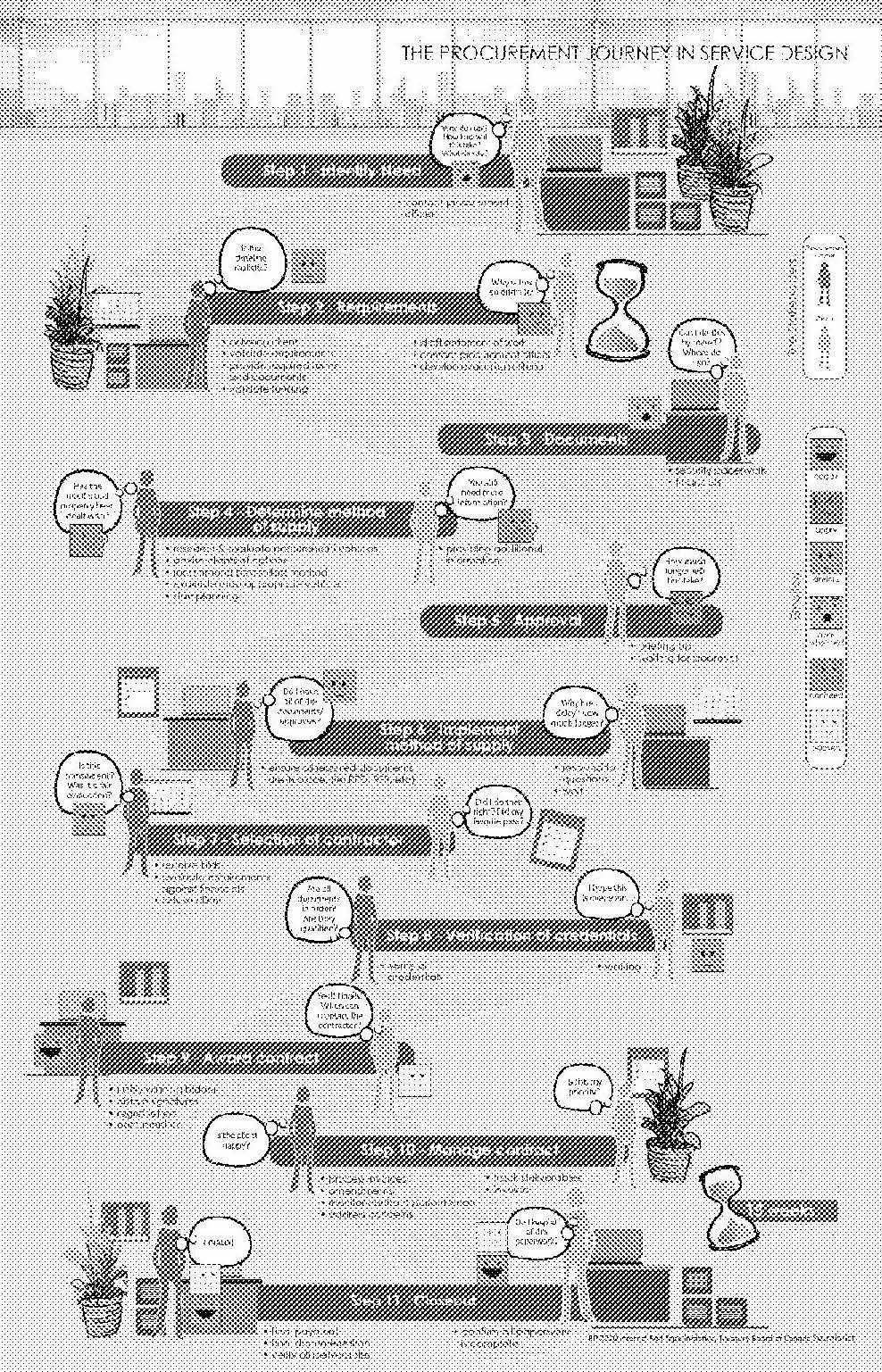

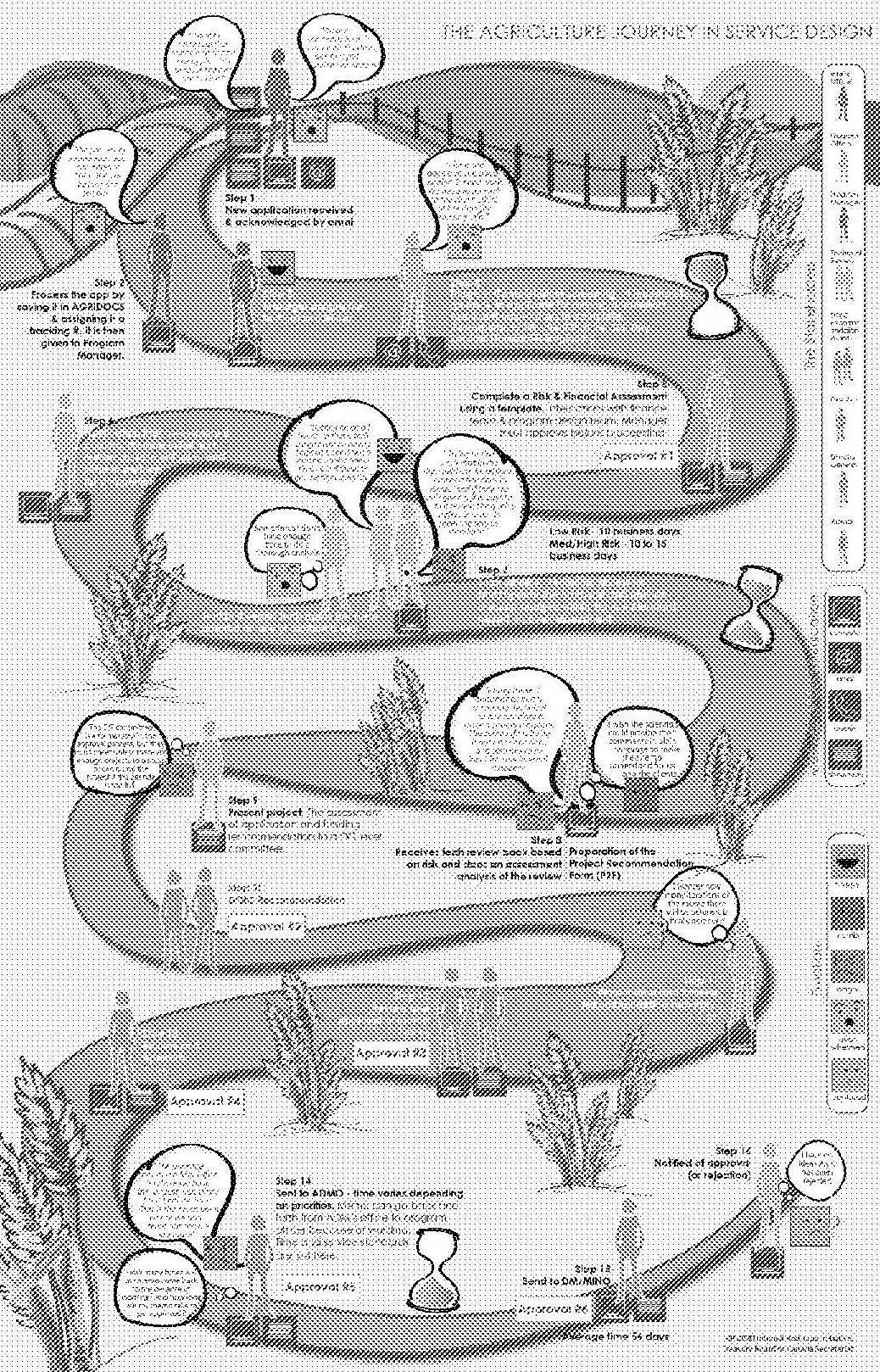

In general, procurement process steps are similar among departments and are already lean. Participants identified 11 common steps for a LDV service contract procurement, entitled “The Procurement Journey” In Service Design (Figure 7). That said, an examination of the cost to a department of an LDV service contract in 2013 suggests that far too much time and effort is spent on implementing this type of contract.

Using Purchasing Activity Report (PAR) data as well as estimated time (touch time and cycle time as per the Lean method) provided by participating departments, the cost (in $ and FTE time) of an average service contract in a department is as follows:

Root causes

Same requirements for million dollar transactions are applied to lDV

Many of the same steps that apply to multi-million-dollar value services are also applied to LDV services, with the same levels of controls in place. The accountability and authority that is expected to be delegated to the manager or director in reality is not, as many levels of approvals are required. This becomes more apparent when the value of the contract is above $10,000 and, as a result, is subject to proactive disclosure. The amount of work and level of scrutiny outweigh the potential risks associated with LDV transactions.

The process for procurement is already lean, as confirmed by the Interdepartmental Working Group members. The complexity of the procurement process is, for the most part, driven by the various rules that apply to procurement, depending on the nature of the service to be acquired, and other provisions including the method of procurement, the credentials of the supplier, security, IT, intellectual property, and the like, which must be taken into consideration as part of the procurement process.

Roles and expectations are unmet

Both the procurement officer and the client have to navigate complex paperwork that requires a substantial amount of time and effort, particularly in the early stages. There are too many “exceptions,” depending on the nature of the service required or the method of supply selected. A “fear of audit” (internal audits, audits performed by the Auditor General of Canada, horizontal audits and others) further drives the need to document every step of the process, which, in turn, drives the heavy paperwork, all in paper format.

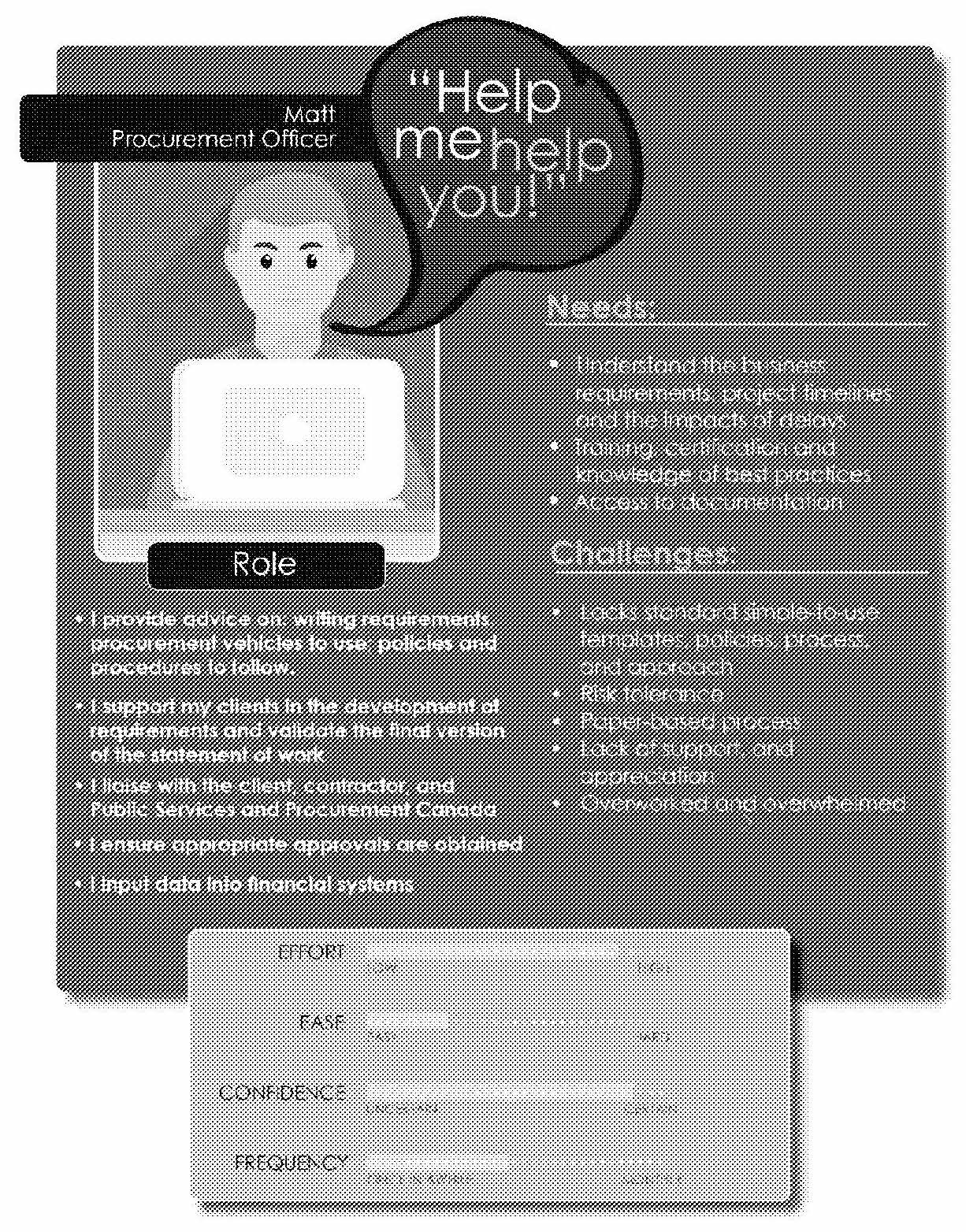

Key to a seamless procurement process is a positive working relationship between the procurement officer and the client. Procurement officers see themselves as experts. They receive regular training, and know the requirements and what the process entails. Most clients have little to no knowledge about the procurement process and expect the support of procurement officers throughout the process.

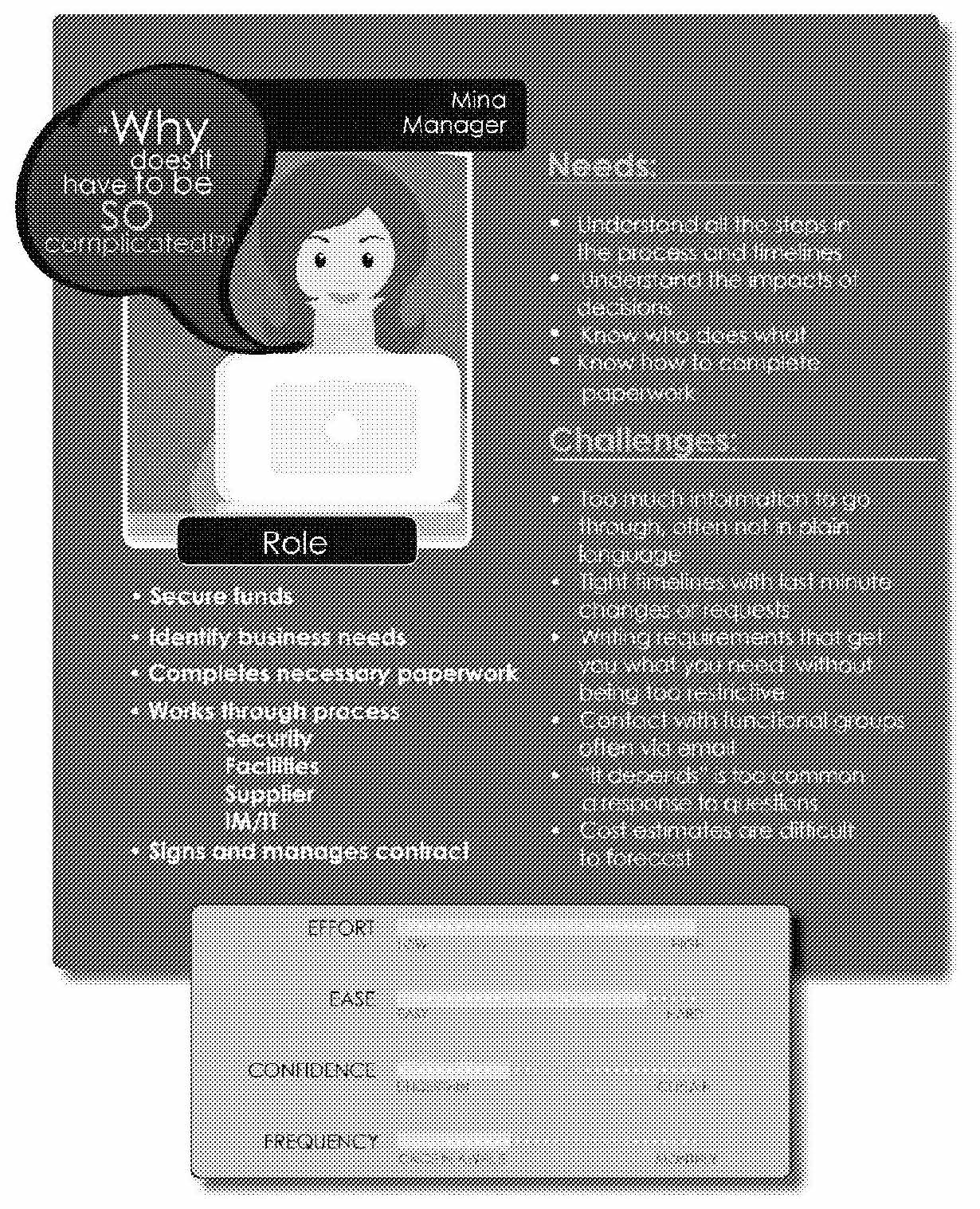

In most cases, procurement officers (Figure 5) do not have the time to work closely with the client. Procurement officers are overwhelmed by the sheer number of requests to be processed, the lack of clarity and the client’s ever-changing requirements. Depending on the department, the level of intervention and support from the procurement officer varies. In an average department, procurement officers process 4,000 to 5,000 contracts for services under $25,000 alone, which helps to explain the immense pressure they feel. As a result, procurement officers do not feel that they have the time to provide support for clients and, often, the two do not have face-to-face meetings or any personal interaction other than by email. They expect the client to have an understanding of the rules, their needs, and the best method to contract the service, relying on advice from the procurement officer only as required. Through the workshop series, it was also mentioned that the turnover rate among procurement officers was high, which could be attributed to them feeling stressed and unappreciated. Lacking knowledge in the area of procurement, the client (Figure 6) feels overwhelmed by the process and the associated paperwork. Getting straight answers is a challenge. For those working in the regions, there could also be delays due to distance. For example, in some departments, regional officers must deal with a procurement officer located at headquarters in the National Capital Region. Participating procurement officers agree that, in procurement, the answer is often “it depends,” as many decisions are made on a case-by-case basis. Clients initiating requests also indicate that, depending on who you talk to, you will receive a different answer; there is no “single truth.”

Clients are generally instructed to “find it (the information) on the website!” However, they indicate that the website (their departmental internal site), when available, is difficult to navigate and not always up to date. In addition, clients are asked to review the entire policy rather than the specific requirements that may apply to their request. Moreover, additional requirements, coupled with a complex set of rules, create unease and uncertainty for the procurement officer and the client alike.

Limited tools to support the process

Managers and analysts have limited tools at their disposal to support the process. The Working Group identified 39 forms and pieces of documentation related to the procurement of an LDV service contract, from initiation of the process through to contract close-out.

Many of the steps are paper-based. Other than committing funds through the financial application system, all procurement-related transactions are paper-based and transmitted by email, as required. All parties to the process must also save and file all forms and documentation in paper format for audit purposes. Electronic signatures are not in effect, and all approvals and contracting related to signed papers are required to have a wet signature and be filed accordingly.

Proposed solutions

A fast track process for service contracts under $10,000

The Interdepartmental Working Group identified the creation of a Fast Track process for LDV service procurement as a solution to prototype and test, making sure to assess gains with respect to time and effort. In practice, a manager would be able to acquire any short-term service regardless of its nature (e.g., facilitation service for a session, one- or two-day training session, graphic design service) and without requiring higher levels of approvals. If the manager has delegated authority, he or she would be able to exercise that authority without additional approvals.

The Interdepartmental Working Group also proposed increasing the threshold for acquisition cards and allowing managers to use their authority to acquire services the same way LDV goods are acquired, with a clear understanding of the requirements.

Improve quality and availability of information

As the procurement officer is expected to play a supporting role, much like a “Sherpa,” enabling the client to climb to the “summit” with a finalized and signed contract, increased collaboration between the two parties would allow for the procurement officer to share his or her expertise and experience along the “climb.” The client would have a better understanding of the process and requirements, and the procurement officer would be able to better understand the client’s needs and provide the best advice.

It was clearly articulated during the workshop sessions that a face-to-face meeting between the procurement officer and the client would be a valuable step, where the client would receive a “walk-through” of the process, which would in turn lead to a more efficient and effective process. However, given that face-to-face meetings are time-consuming, that procurement officers have a number of contracts to process and that they already feel overwhelmed, the Interdepartmental Working Group proposed reserving face-to-face meetings for larger, more complex contracts, and focusing efforts on improving the quality and availability of information on departmental websites, via user guides and how-to videos, to help bridge the gap in knowledge between the procurement officer and the client.

Develop an online application system

While most transactions and documents are paper-based (among the participating departments, only Infrastructure Canada has an electronic system that supports initiating and tracking a contracting request), all participants agreed that having an online application system, including required templates and a built-in approval system, would improve the process significantly. An online application system would, however, be limited until it was equipped with an electronic signature, given the auditable nature of each step and the need for wet signatures as a condition, especially with respect to delegated financial authority.

Initiatives under way

The Tiger Team is aware that Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) is currently working on developing an Electronic Procurement Solution (EPS), or e-procurement, which, once fully rolled out, is expected to streamline the procurement process using a single portal. The e-procurement system would be designed to support a procurement request from the needs identification phase through to contract award, with built-in templates and audit records, and to act as a single source of truth for procurement in the Government of Canada and as a single source of disclosure for all provincial, municipal and federal awards. With this being a technological solution, it will be important that it receive ample user testing and sufficient time and resources dedicated to its implementation.

Staffing stream findings

Participating Departments

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Natural Resources Canada

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

Central Agency Partners

- Public Service Commission of Canada

- Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer

Scope: Internal advertised staffing process with a national area of selection

Background

Human resources management, particularly within the area of staffing, has undergone a tremendous amount of change over the past decade in an effort to modernize and provide more flexibility. Primary among these changes was the introduction of the Public Service Modernization Act (PSMA), which was passed into law in 2003 and enacted two major pieces of legislation: a new Public Service Labour Relations Act and a new Public Service Employment Act (PSEA). These legislative changes were intended to

“create a more flexible staffing framework to manage and support employees and to attract the best people, when and where they are needed; foster more collaborative labour-management relations to ensure a healthy and productive workplace; and clarify accountability for deputy heads and managers.”

Significant investments were made across the public service to implement the new legislation, including changes to the machinery of government, the creation of new mechanisms and processes, and investments in training human resources staff and hiring managers. However, a review of the PSMA conducted in 2011 found that the federal public service still faces many of the same people management challenges it did before its introduction. The PSMA Review Team concluded that further legislative change would not be necessary. Rather, non-legislative changes, such as a sustained commitment to behaviour and culture change, offered greater promise. It further cautioned that, while new tools, processes, technology and organizations may also be required, they would not be sufficient on their own and could not substitute for real changes to behaviour.

Key roles and responsibilities

The Public Service Commission (PSC) has the mandate to promote and safeguard merit-based appointments, as set out in the Public Service Employment Act. It delegates staffing authority to deputy heads but provides policy guidance and expertise, conducts oversight of the overall staffing system, and reports on its mandate to Parliament. The PSC also works with other stakeholders, such as the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO), acting on behalf of Treasury Board (TB) – which is the Employer of the core public administration – to support a high-quality workforce and workplace.

The problem: The process takes too long to complete

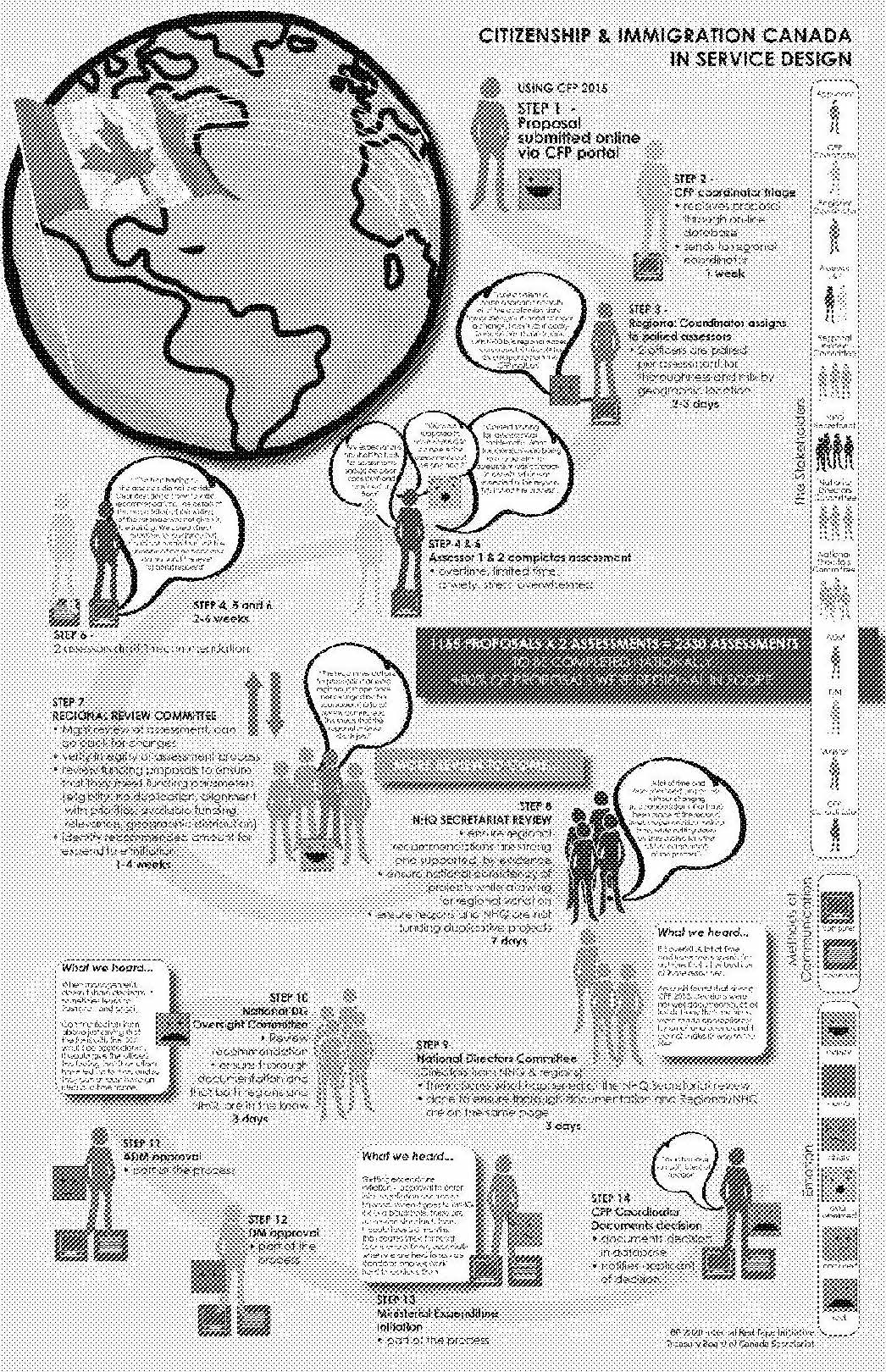

The Working Group collaboratively mapped out the steps for an Internal Advertised Staffing Process (Figure 8) with a National Area of Selection. A full-size version of the staffing process depicted to the left is available at the end of this section.

On average, there are 50 to 75 steps in the internal staffing process, amounting to an average of 40 weeks to complete. Figure 8 provides the complete mapping of the Internal Staffing Process. As shown in the table below, many of the processes can be simplified through Lean methods.

- Average time to staff = 40 weeks

- Number of steps in the process = 50 to 75

- The most time/effort-intensive phases of the process are:

- Development of the Statement of Merit Criteria and assessment tools = 2 to 3 months

- Priority Reviews = 2 to 4 weeks

- Initial screening = 3 weeks to 2 months, depending on volume

- Assessment (exam plus interviews) = 2 to 8 weeks

- Average number of days that can be reduced through eliminating waste via lean methods = 20 weeks (i.e., half)

Root causes

While heavily rule-bound, flexibilities exist but are not being fully used

According to the Working Group participants, the current rules provide enough flexibility, and this flexibility could be better leveraged. That said, departments, being risk averse, are generally hesitant to use them. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of the review of the PSMA.

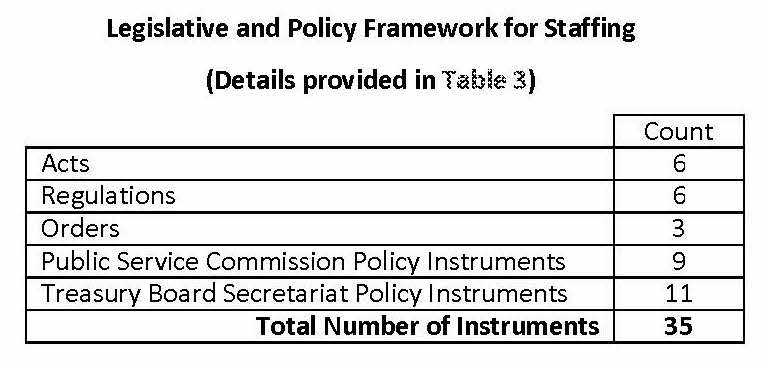

Staffing is a complex policy area governed by a mix of rules ranging from legislation (both direct and indirect) to prescriptive policy guidance – an estimated minimum of 35 instruments, as listed in the table, not including related areas such as security clearance or procurement of services. However, when the Working Group conducted a “task decomposition” exercise to gain a better understanding of the “drivers,” or motivating factors, behind each action (or step) performed as part of an internal advertised selection process, very few actions were required by a rule. Instead, the majority of steps taken in a staffing process can be attributed to departmental practice, or are simply the result of how things have traditionally been done.

One such step is the assessment process. Here, candidates are first assessed through their application, and then issued a written exam, followed by an oral exam, reference checks, and an interview. A great deal of discussion within the Working Group focused on why there needs to be so many layers of assessment, and whether this sequential, step-by-step approach is the best way to evaluate candidates or whether more global assessments would be more effective. The managers interviewed also stated that they would like to further explore the use of a candidate’s past performance (e.g., performance management results) or on-the-job observations (e.g., in cases where someone has been acting in a position) to either replace or supplement traditional assessment methods.

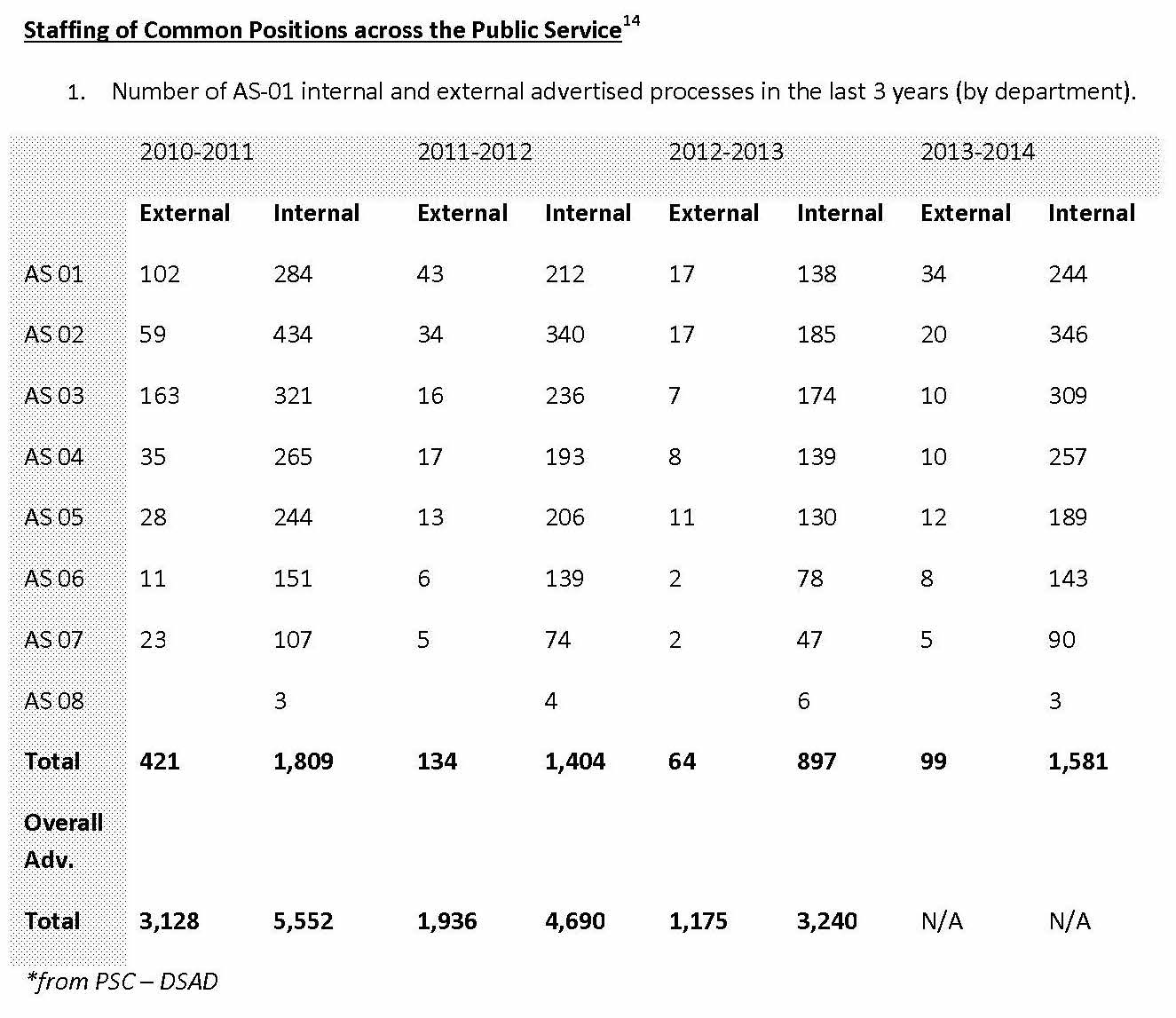

Lack of clarity about available tools and insufficient infrastructure

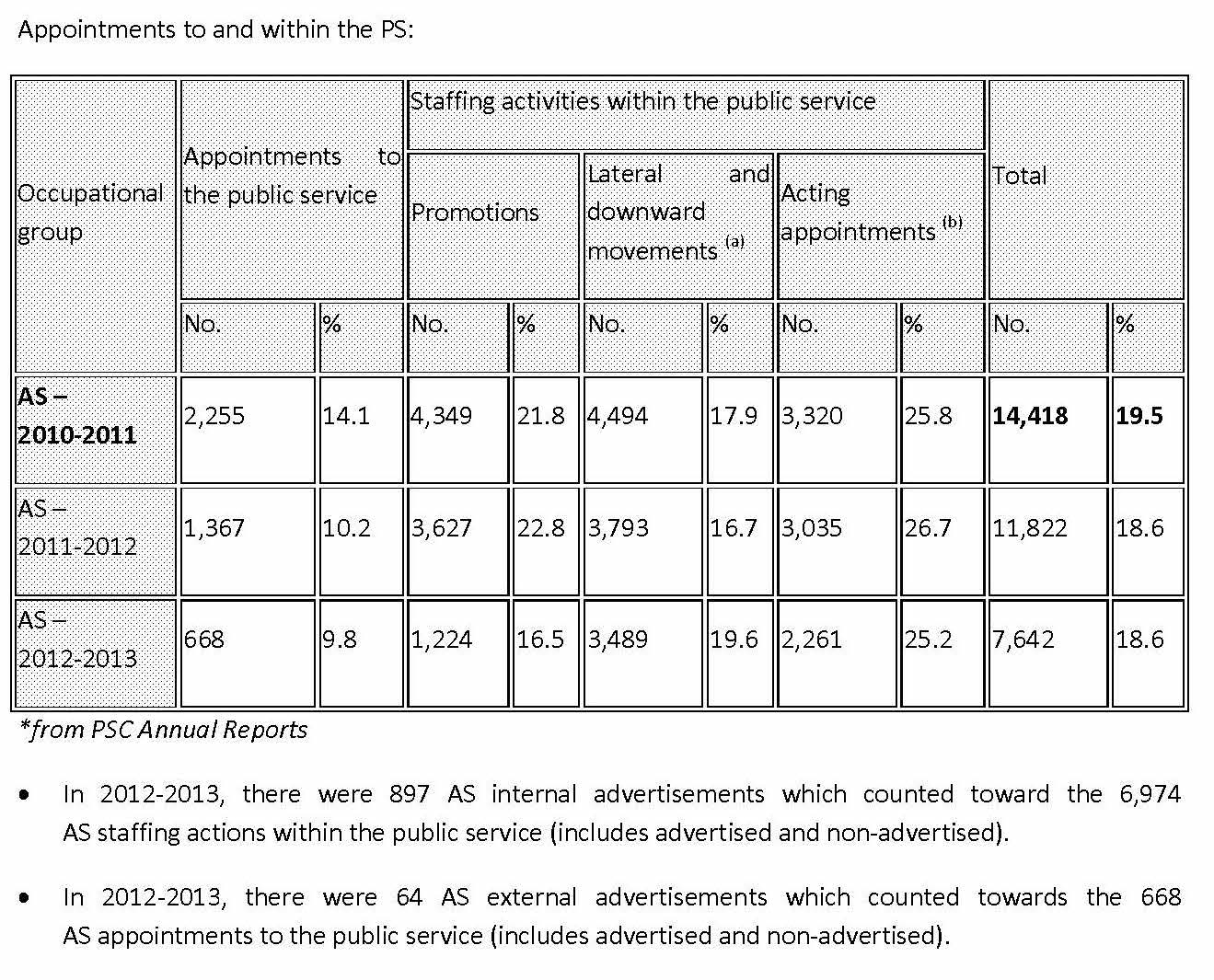

A significant amount of effort is spent on staffing common “entry-level” positions using individual selection processes across departments in the public service. For instance, in 2012-2013 alone, 138 internal AS-01 advertised selection processes were conducted. This raises questions about whether there is a sound rationale for conducting separate processes, given that the positions do not require specialized knowledge. If the average cost to run a selection process is $13,910, approximately $1.9M is spent annually to staff the most common entry-level positions in the public service. Additional details can be found in Table 2.

Notwithstanding the availability of some tools, the Working Group participants and the clients they interviewed expressed their frustration with not having access to a broader set of standardized public service-wide tools and templates. This can be attributed, in part, to the fact that deputy heads have delegated authority for staffing within their own departments, which means that individual departments may develop their own materials despite that many positions – particularly entry-level ones – are common across the Government. Several of the participating Working Group departments, including Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), and Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), are currently working on building their own repositories for certain tools (e.g., Statement of Merit Criteria inventory, Student Bridging database, Letter of Offer builder). There was significant interest in the central agency partners establishing a public service-wide database or platform.

Absence of strategic planning and data analytics

As the baseline data shows, a significant proportion of time during a staffing process is spent in the upfront planning stages; in other words, before the selection process is even advertised. This includes corporate-level business and workforce planning as well as process-specific planning, including the design and roll-out of the staffing process and the development of materials (e.g., the Statement of Merit Criteria and assessment tools). Working Group participants spoke at length about the lack of knowledge on how to conduct proper planning as well as the lack of attention paid to planning, both on the part of Human Resources (HR) advisors and the hiring manager. The result is that staffing does not tend to be linked strategically to departmental priorities and plans.

Roles and responsibilities in conducting HR activities and HR planning, in particular, are not well-defined in departments. Who does what is often negotiated ad hoc and based on the availability of resources at that point in time, rather than planned in advance. All of the participants agreed that a lot of time is wasted as a result of back and forth interactions among managers, their administrative staff and HR advisors.

In addition, while HR provides hiring managers with planning templates to fill in, often there is little in the way of supporting context, data, or analysis. Managers fill in the templates to the best of their ability, using their best guesses as to what their staffing needs will be, in the absence of data analytics, workforce forecasting, turnover rates and the like.

Several of the managers interviewed indicated that having access to integrated HR data that is linked to financial information, as well as historical trends, business and workforce needs analyses, and forecast data would help them conduct proper planning. While the HR experts in the working group agreed that HR should help fill this gap, they note that there is very limited capacity and a lack of the necessary skills within their shop to do so.

While digging even further at the root causes of poor planning, it became apparent that a lack of consequences for the hiring manager and HR advisors alike – or, put another way, the absence of a clear incentive to do planning – may help explain this. There is no legislative or policy requirement to develop departmental HR plans. At the same time, HR is often so busy working on operational tasks that planning becomes a lesser priority.

HR advisors performing a “policing function” rather than acting as a “business partner”

As indicated previously, a lot of time is “wasted” in the staffing process owing to back and forth interactions between managers and HR, which is especially true in cases where tools and materials are not planned in advance, are developed incorrectly, or need to be revised or replaced mid-process. While poor planning is a major contributing factor, the root cause goes deeper.

Stakeholder mapping, Working Group discussions and user interviews revealed that there is an absence of trust among the parties, and thus little partnership. The lack of trust exists on both sides, with managers believing that there is little value added from consulting with HR and thus only consulting their services when absolutely necessary, and with HR believing that managers are not forthcoming about what their real staffing needs are. The absence of trust, coupled with a risk-averse culture, means that HR tends to perform a “policing” function rather than act as business partner, anticipating the staffing needs of clients and providing strategies for workforce management, such as recruitment, talent management and employee mobility.

Varying levels of dedicated resource

A common observation from Working Group participants and clients was that having a specific resource to lead and oversee the staffing process was critical to shortening the time it takes to staff. It does not appear to matter whether this dedicated resource is an administrator, a manager, an HR staff member, or even a hired third-party consultant. What does seem to make a difference is the level of commitment to the staffing process and to viewing its operation and completion as a high priority, as well as support from senior management to spend the necessary time to do staffing. We heard that there is wide variation in the amount of time an internal advertised staffing process could take – as little as two months when there is a high level of commitment among the parties involved and a dedicated resource to oversee the process, to more than six months when the process is not well planned and roles, responsibilities and activities are negotiated ad hoc.

The findings also point to a capacity issue within HR shops, where resources are chiefly devoted to operational and transactional activities as opposed to relationship-building or proactively providing strategic advice. In conducting the root-cause analysis, 11 Working Group participants cited the following as causes for the lack of strategic capacity within HR:

- High rates of turnover;

- HR advisors in the Personnel Administration (PE) occupational group being promoted too quickly;

- Not hiring for the right skills and competencies, such as analytical ability, problem-solving and strategic thinking;

- Lack of targeted training opportunities for HR advisors to improve their strategic capacity;

- Working in silos, little exposure to the breadth of HR functions/disciplines, and limited access to the business realities of the organization (HR advisors do not have a good sense of what their clients do or what their business and workforce needs are); and

- Too much pressure to deliver on the transactional side.

Risk aversion due to a fear of audit

Both the Working Group members and the hiring managers interviewed highlighted a culture of risk aversion within staffing and, more broadly, in HR. More particularly, HR has a fear of being audited by the PSC and found of wrongdoing, which hampers its provision of advice for managers on the full range of staffing options and flexibilities. Instead of outlining all relevant possible options to managers based on their needs, and highlighting the benefits and risks associated with each one, HR advisors tend to default to running full advertised processes. This is especially common when the HR advisor and hiring manager are both inexperienced in staffing.

At the other end of the spectrum, experienced hiring managers tend to request other, typically perceived-to-be “higher risk,” staffing options, such as non-advertised appointments, but are often “blocked” by HR. This disconnect may be explained, in part, by the fact that delegated hiring managers are rarely involved in the PSC’s audit process, even though they are accountable for their staffing decisions. It is usually HR that is the key point of contact for the Commission and that must provide all the documentation and justifications for the staffing action. Often, hiring managers do not know that one of their staffing decisions has been audited. Even in cases of wrongdoing, there may be little in the way of consequences for delegated managers, either because they no longer work in the department, or they receive a simple reprimand. Usually, HR bears the brunt of the audit. Only on very rare occasions, and usually with repeat poor behaviour, do hiring managers have their delegation revoked.

As a result, HR focuses heavily on ensuring that everything is documented, sometimes leading to over-documentation, which slows down the process. HR advisors also tend to avoid performing higher risk staffing actions and using alternative sourcing methods, except in cases where there is support from senior management. The leadership of senior management is important to note here. While the PSEA recognizes that staffing authority should be delegated to the lowest appropriate level, many departments have additional internal controls in place, such as ADM-level committees for all new indeterminate appointments or acting appointments over 12 months.

One could assume that this risk-averse behaviour developed in response to negative experiences and/or a high incidence of wrongdoing. However, in the past seven years, the overall rate of staffing complaints has been extremely low, varying between 0.02% and 0.04% of all internal appointments. In 2013-2014, there were only 495 complaints out of 19,406 internal appointments (0.02%). Furthermore, over 80% of all staffing complaints were ultimately resolved through mediation.

Proposed solutions

Encourage the PSC to continue and augment its work with departments in the adoption of the New Staffing Framework

One recommendation is to encourage the Public Service Commission (PSC) to continue and augment its work with departments in adopting the “New Direction in Staffing,” prioritizing efforts to enable the needed culture shift and achieve a streamlined, modernized approach to staffing. The PSC recently transformed its entire Appointment Policy Framework, including the oversight/audit approach, significantly loosening its control over how departments choose to conduct their staffing. In December 2015, the PSC released a New Direction in Staffing (NDS), to be implemented in April 2016. The decision to move to the new direction is based on the Commission’s conclusions that “the staffing system is mature, demonstrated by ten years of oversight results;” and that “organizational audits and DSAR [Departmental Staffing Accountability Reports] show frameworks [are] in place and working.”

While the New Direction in Staffing does not change any of the existing acts, regulations or orders, the Commission’s Appointment Policy has been significantly streamlined. The key message is that authority/accountability, and flexibility by association, has shifted from the Commission to deputy heads. Chief among the changes are the following:

- Increasing discretion for deputy heads to establish their own organizational staffing frameworks;

- Shifting responsibility for monitoring to deputy heads, with a reduction in reporting requirements to the PSC; and

- Increasing delegation of authorities from the PSC to departments (e.g., the authority to extend the agreement to become bilingual for non-imperative appointments for positions in the EX group may now be sub-delegated to the Assistant Deputy Minister level).

It remains to be seen how departments will respond to the new direction and the extent to which they will utilize the added flexibilities given to them as they design their organizational staffing frameworks. It is hoped that departments will use the results gathered through the Internal Red Tape Reduction Initiative to inform these designs, particularly as they relate to incorporating the user’s perspective. In order to help departments successfully implement the new Staffing Framework, PSC should leverage the opportunity and work with departments by mentoring the design and implementation of new options to create the change required in the current culture as well as to incentivize desired behaviours.

Support the role of HR as a “business partner”

A key theme that emerged in our Working Group activities and discussions was that the expectation of the services HR should be in the business of providing has shifted over time. In the 1990s, HR shops were organized by client portfolios with dedicated HR advisors who understood the business of their clients and had the capacity to provide expert advice. Over the years, and particularly during and after the Deficit Reduction exercise, there was a push to reduce spending on internal services. The emphasis was on finding technological solutions and increasing efficiencies through automation and self-service, which resulted in a shift in the service model. HR shops across government were consolidated and/or centralized and reduced in size, and the work traditionally performed within HR shifted to be carried out by managers or reassigned to administrative staff. In many instances, departments changed their organizational structures to put in place groups of administrators that would handle the coordination of certain HR and financial processes, sometimes referred to as “shadow shops.”

In user interviews, hiring managers shared that they felt that HR is no longer able to provide the services that they expect, that HR is often out of touch with their clients’ business, and that they possess limited expertise in providing strategic advice. This was validated by the Interdepartmental Working Group participants, who were honest in stating that they are encountering difficulties in defining what the business of HR should be, and in building up a sufficient level of capacity among the staff. They noted that a large proportion of HR staff are so used to performing transactional work that it will be a challenge to change current behaviours. At the same time, however, there is a sub-population of HR advisors who are eager for change and want to be provided with the freedom, trust and time to take on a strategic role and build partnerships with their clients.

In the short term, HR managers can begin by exploring options for improving the strategic capacity within their shops and opportunities for enriching their HR advisors’ current skill sets, via recruitment, and training and development planning, such as the course offerings on human resources planning, and providing strategic advice at the CSPS. Equally important is the Government giving consideration to providing training in data analytics that is specifically geared to the HR practitioner.

Clarify behaviours expected of HR advisors

Ultimately, however, any shift in the HR function needs to be firmly grounded in a clear understanding of what types of behaviours are expected of HR advisors in their current environments; what types of deliverables or actions are rewarded and what types are discouraged, either overtly or inadvertently; and what behaviours HR advisors are assessed against in evaluations of performance.

The fields of psychology and behavioural economics may offer some insight into why the staffing system has been slow to change despite various legislative (e.g., the Public Service Modernization Act) and process changes (e.g., implementation of Common HR Business Processes) and may, more specifically, help to understand the important questions that this work raises, such as:

- Why departments are not maximally using the staffing flexibilities available to them;

- Why the focus of HR continues to be transactional work and documentation despite client requests for advice and partnership;

- Why HR is risk averse when there are few instances of staffing complaints;

- Why departments continue to have in place burdensome internal controls when the temporal requirement/risk (e.g., Deficit Reduction) has passed; and

- Why legislative, process and structural modernization efforts (such as the PSMA, and implementation of Common HR Business Process and PE Generics and job descriptions) have not had the desired effect of improving HR services and shifting the culture of HR.

As the literature suggests, individuals have a tendency to prefer the current state of affairs, having what is called a status quo bias, where the current state is perceived as superior even in the presence of available alternatives. Status quo bias interacts with other non-rational cognitive processes, such as loss aversion. In prospect theory, the phenomenon of loss aversion is described as the tendency for people to have a strong psychological preference to avoid losses over acquiring gains. Research suggests that losses can be twice as powerful psychologically as gains, which helps to explain the aversion to taking risks, particularly if we also consider the effects of the principle of availability. Availability refers to the fact that events that more easily spring to mind, such as recent, traumatic or burdensome events (e.g., being audited by the Public Service Commission) will have more of an influence on our behaviour. This may help explain why HR continues to assume a policing role – in response to a fear of audit – thus perpetuating the over-documentation of staffing files and limiting the use of flexibilities available to them and their clients.

The adoption of a behavioural economic lens may help to design and put in place either

- The right economic incentives for behaviour change, such as changing what aspects of HR services are monitored and measured (quantitative service standards, including response time, time to staff, etc., and qualitative measures, including quality of advice, dependability, quality of hire, etc.). Reviewing what objectives are measured in employee performance management agreements may also be a fruitful exercise; or

- Subtle “nudges,” which take less effort to implement and influence behaviour primarily by changing the way that choices are presented in the environment. This could include making available key pieces of information or framing the information in such a way that actors can make better informed decisions (e.g., demystifying the risks associated with certain staffing options, as a start).

Initiatives under way

There are currently a number of large government-wide transformation efforts taking place in staffing and in people management, more broadly including

- The PSC’s new direction on staffing;

- The implementation of My GCHR and Phoenix pay systems;

- The Interoperability and Business Intelligence project to link and enable data flow among various HR-related IM/IT systems;

- Treasury Board Secretariat’s Policy Reset, which includes a full redesign of the existing suite of people management policies, among other policy areas;

- A new curriculum at the Canada School of Public Service for HR practitioners; and

- Ongoing work by the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer to transform HR services and to keep the Common HR Business Processes current.

At the same time, departments are working to redesign their own organizational staffing frameworks to increase efficiency, efficacy and workforce agility.

Each of these projects offers an opportunity to apply the learnings gathered through the Internal Red Tape Reduction Initiative and to shift the incentives in the system to effect real behaviour change and, ultimately, strike the appropriate balance between control and the provision of the level and type of service that clients expect, including strategic advice.

Table 3: List of Staffing-Related Acts, Regulations and Central Agency Policy Instruments

- Acts (6)

- Canadian Human Rights Act

- Employment Equity Act

- Official Languages Act

- Public Service Employment Act

- Public Service Labour Relations Act

- Public Service Labour Relations and Employment Board Act

- Regulations (6)

- Public Service Employment Regulations

- Appointment or Deployment of Alternates Regulations

- Indian Affairs and Northern Development Aboriginal Peoples Employment Equity Program Appointments Regulations

- Locally-Engaged Staff Employment Regulations

- Public Service Official Languages Appointment Regulations

- Student Employment Programs Participants Regulations

- Orders (3)

- Appointment or Deployment of Alternates Exclusion Approval Order

- Public Service Official Languages Exclusion Approval Order

- Student Employment Programs Participants Exclusion Approval Order

- Public Service Commission Policy Instruments (9)

- Appointment Policy Framework

- Official Languages in the Appointment Process Policy

- Area of Selection Policy

- Priority Administration Directive

- Guide on Priority Administration

- Appointment Delegation and Accountability Instrument

- Advertising in the Appointment Process Policy

- Policy on Employment Equity in the Appointment Process

- Guide to Implementing the Policy on Employment Equity in the Appointment Process

- TBS Policy Instruments (11)

- Values and Ethics Code

- Policy on the Duty to Accommodate Persons with Disabilities

- Employment Equity Policy

- Student Employment Policy

- Policy on Interchange Canada

- Directive on Interchange Canada

- Term Employment Policy

- Terms and Conditions of Employment for Students

- Terms and Conditions of Employment

- Directive on Terms and Conditions of Employment

- Policy on Conflict of Interest and Post-Employment

Grants & Contributions Stream Findings

Participating Departments

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Canadian Heritage

- Infrastructure Canada

Scope: The grants and contributions process

Background

Transfer payments are a key instrument for furthering the Government of Canada’s broad policy objectives and account for a large part of government spending. In 2014-2015, the Government issued approximately $143 billion in transfer payments,15 the majority of which were transferred to other levels of government and individuals through programs with ongoing spending authority. However, a significant portion – $26.2 billion – was transferred through Grant & Contribution (G&C) agreements.

Projects funded through federal G&C agreements are diverse and have a direct impact on Canadians where they live and work. They range from services and support for new immigrants, to health research and employment programs, to investments in the responsible development of natural resources. Recipients of Government funding work with the Government as a partner in the pursuit of shared objectives, including the promotion of Canada’s economic and social development. By properly managing G&C programs, the Government is able to provide efficient, effective programs that are responsive to the needs of Canadians, while ensuring accountability for the proper use of public funds.

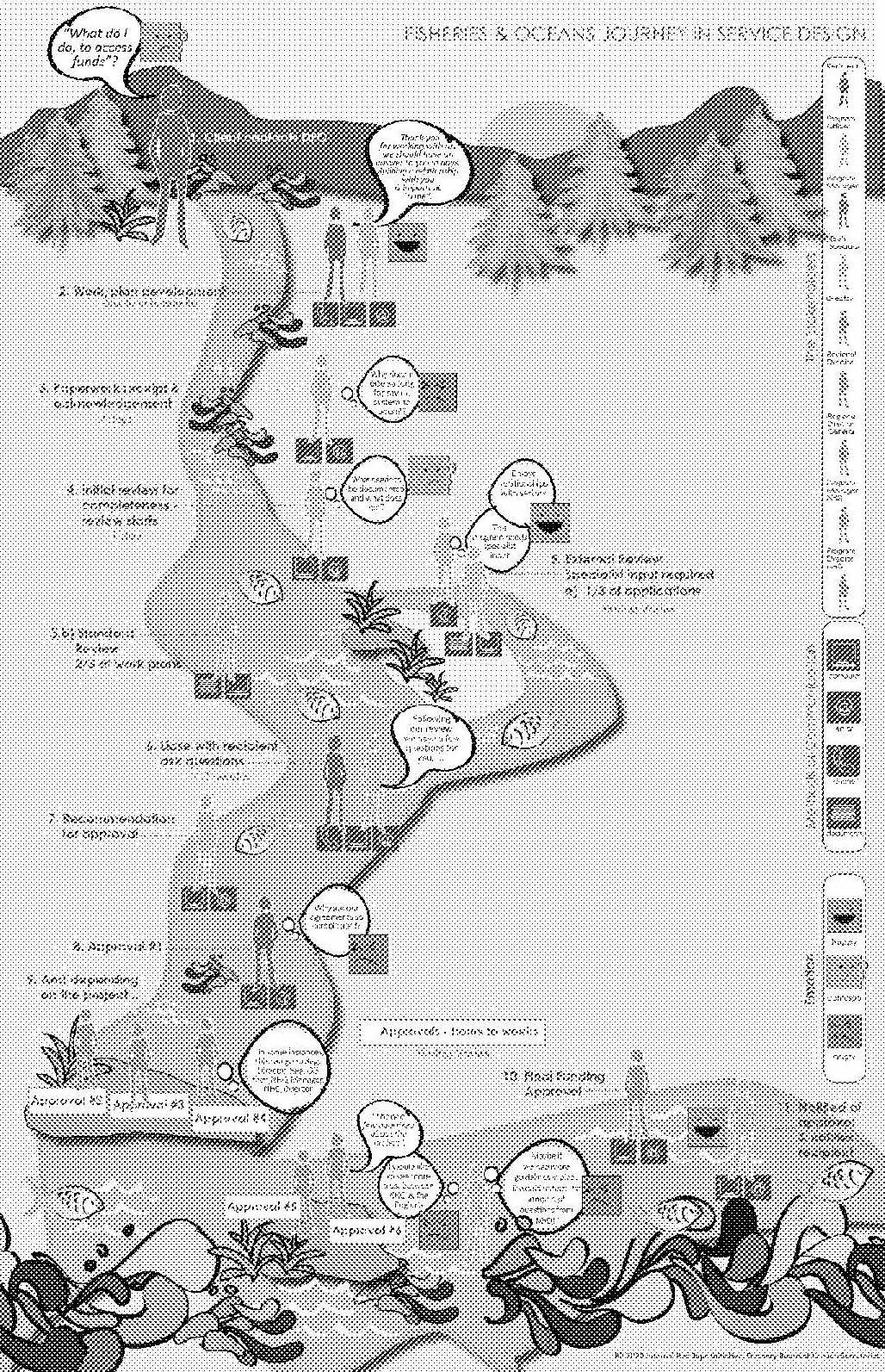

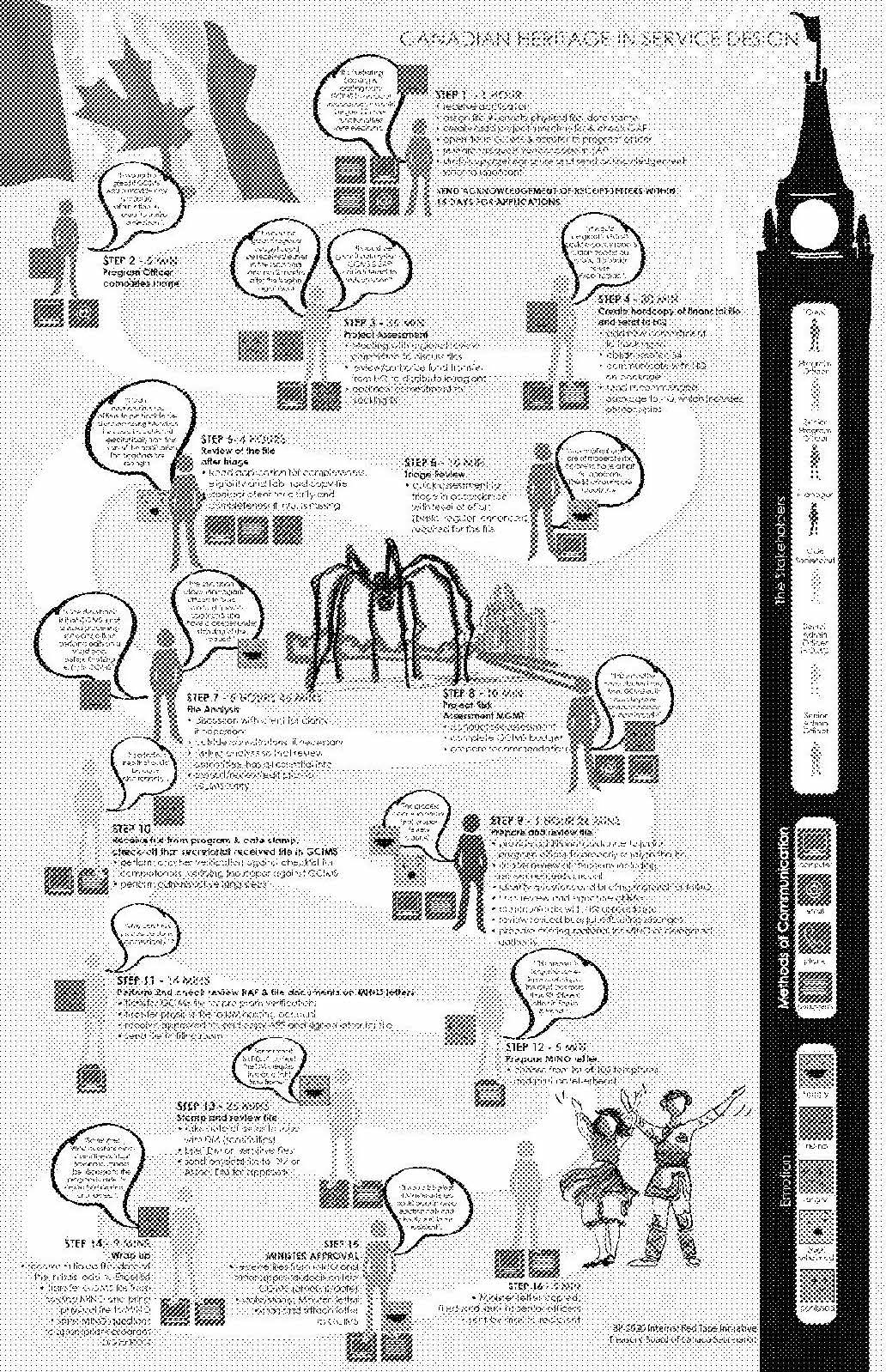

The problem: One size fits all assessment

The Tiger Team found that, in participating departments, every application, regardless of size, complexity, or history with the department, is assessed in exactly the same manner, with the same level of scrutiny. However, departments have been moving to a more risk-based approach, as requested by the policy on transfer payments. Canadian Heritage appears to be the most advanced in this regard, with a “triage” system in place that is applied upon receipt of the application in order to assess its complexity and the amount of time it will likely take to move through the process. Some of the participating departments indicated that a triage system could assist them in streamlining their process, and that they would be making a proposal to their senior management.

Root causes

Additional safeguards with no value added to the process

There are a number of mechanisms in place to safeguard taxpayers’ resources.

These mechanisms range from restricted delegated approval levels to the establishment of various review committees. Participants agree that having the appropriate safeguards in place is necessary to ensure that resources are properly accounted for and disbursed in a fair and transparent manner. However, there was consensus that, in many cases, additional safeguards do not add value to the process, and that it would be appropriate to review existing approval processes to determine whether streamlining is an option.

Technological systems not designed with users in mind

All Working Group participants agree that the current technology was designed without a clear understanding of how the user navigates the business process, and with assumptions about the user’s comfort level with technology. The result is that many users are not as “technologically savvy” as expected, and therefore tend to under-utilize the tool.

Furthermore, the Working Group noted that, for some departments, the standardization of forms means that substantially more information is requested than what is needed to make a funding decision. In addition, “random questions” from review committee members, by default, often become a permanent part of the information gathering exercise, thus feeding the collection of extensive documentation that may or may not be used in the assessment. As a result, program officers spend an inordinate amount of time assisting applicants in piecing together this unused information and entering it into IT systems, which, for the most part, are not designed to house large amounts of data.

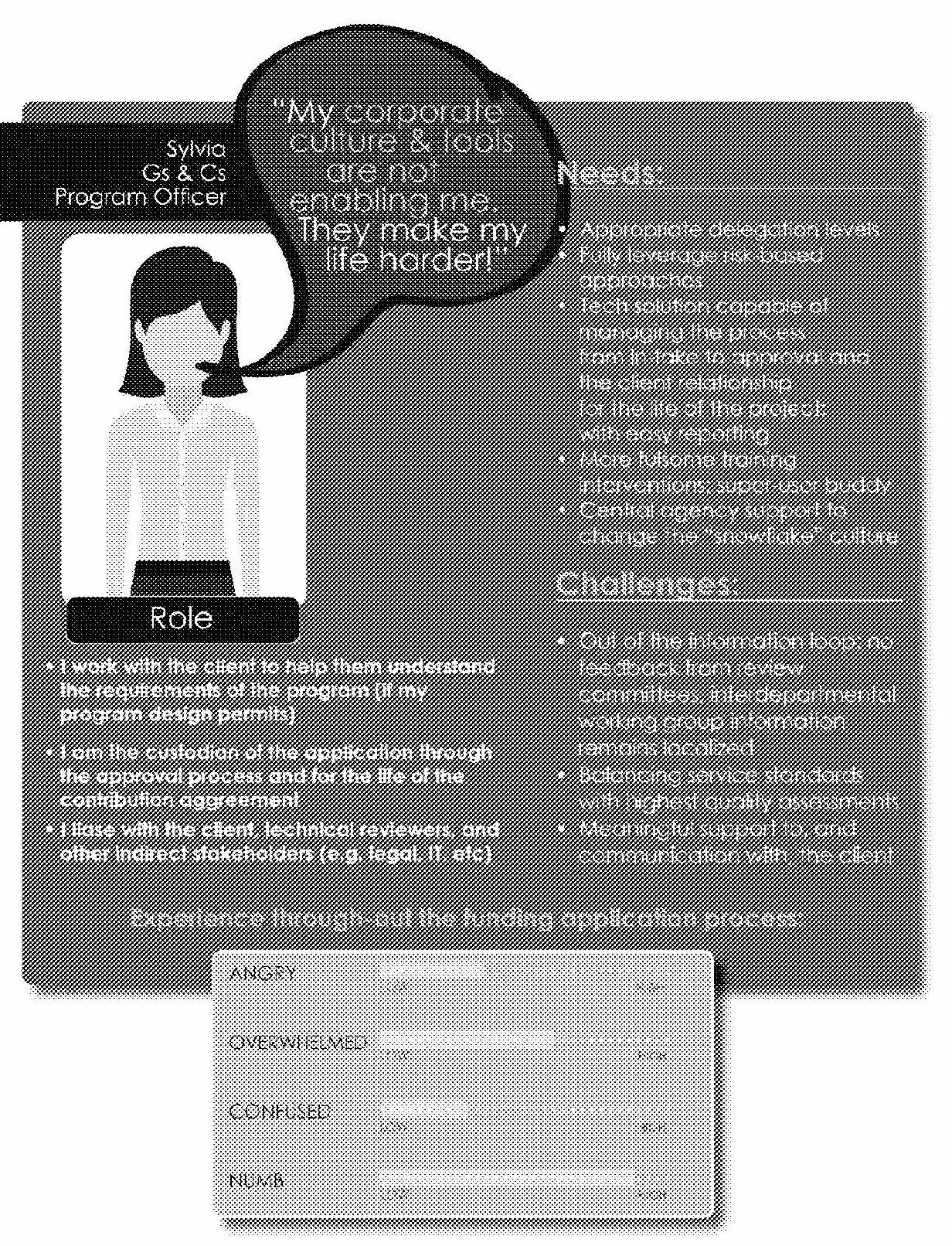

Disconnect between program analysts and departmental decision-making processes

During the interviews, there was a great deal of feedback around the lack of transparency and openness within departments, as well as externally with clients. This was a common theme that emerged across all the interviews, with slight variations by department. It was noted that information was not always, if at all, disseminated to the program officer in a timely manner. This has a direct impact on the ability of program officers in most participating departments to also provide timely information for their clients (Figure 14). More particularly, once an application moves to the approval stage at senior levels of the department, program officers often lose track of the file, with the result that they are unable to update their clients accordingly. While participating departments have systems that are able to track internal movement, they are generally ill-equipped to provide detailed information about the status of the application at that stage. Interviewees reported that the results of various working group discussions often remain localized, with the outcomes not being widely disseminated, leaving program officers with the feeling that they are being left behind by the “process.” As part of the workshop, the persona (Figure 14) of the program officer was mapped out to gain a better understanding of the program officer’s role, needs and challenges.

Proposed solutions

Improve delegation of authorities

The Working Group recommended that discussion take place within departments, including at the Ministerial level, where appropriate, to examine the current delegation of authority and explore options for improvement. More specifically, the Working Group suggested discussion around the following:

- Adopting the Principle of Subsidiarity, where the aim is to “ensure that decisions are taken as closely as possible to the citizen.”

- Reviewing the delegation architecture of other public service G&C programs to identify best practices, as well as the impact of service standards on the applicants’ operations and the Government’s mandate, if any.

- Modifying the role of the review committees from approval-based to reporting and/or oversight, as well as moving the committees to the front end of the process to better use their feedback and improve communication.

- Random sampling of approved applications to assist in the development of baseline data to identify trends or issues that require attention.

Over the long term, the Working Group urged that consideration be given to ensuring that a systemic approach to critically assessing the positive and negative effects of proposed and existing regulations and non-regulatory alternatives (similar to a Regulatory Impact Analysis) is performed before implementing any new processes. Doing so would help to ensure that no additional administrative burdens are introduced without fully considering the impacts. In the meantime, participants underscored the need for further analysis of the relationship between audit and red tape to gain a better understanding of the nature of this relationship.

Review the delegation architecture of other public service G&C programs and apply similar parameters

At the onset of this project, one of the fundamental assumptions the workshop participants held was that the Transfer Payments Policy (TPP) was a significant “pain point.” To test the validity of this assumption, the Tiger Team mapped out the steps performed during the application process with the requirements of the TPP and the accompanying Directive. Participating departments were also asked to specify which part of the TPP was a concern. After discussion and analysis, Working Group participants concluded that while challenges exist within certain parts of the TPP, the TPP is not a “pain point” in the application process. “Pain points” are driven by department-imposed steps rather than mandatory Treasury Board oversight mechanisms.

The Working Group recommended that departments engaged in grants and contributions inventory and examine the non-obligatory and informal approvals currently in place and “challenge” their practice within the G&C process. The Working Group further recommended that Treasury Board continue to engage stakeholders around changes to the TPP and its related instruments, with the goal of ensuring that the policy is well understood by the users.

Timely status updates for clients and program officers

Working Group participants recommended that departments review and ensure that communication protocols for providing clients with timely updates about the status of their application at all stages of the process are in place. Doing so would serve the two-fold purpose of safeguarding the openness and transparency of the process and bringing program officers back into the process, thereby returning to them a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment in seeing the results of their work with their clients firsthand.

Empathy for program officers